Some might find this an essay on a trivial subject—a one-hundred-year old personal debt. How this debt is interpreted, however, defines the nature of the relationship of two men: Takeda Sokaku and Ueshiba Morihei. It is remarkable how an assertion, however small, can create—or at least confirm—a myth. In this case, the myth is the domineering relationship of Takeda Sokaku towards his student, Ueshiba Morihei, and that, even further, Sokaku was grasping, even greedy. The account of this allegedly unfair debt is used to buttress the claim that Takeda Sokaku intrusively, inescapably controlled Ueshiba’s life. For partisans of Ueshiba, he is perceived to be somewhat of a victim, bound by honor and loyalty to a teacher who made surpassingly unreasonable demands upon him.

To merely recount a story of a man who found a teacher, studied various wrist-locks, throws and pins, and came up with some new interpretations on how to do the same techniques is all too mundane. The birth of aikido, viewed as an art of spiritual transformation, and an invincible, unique martial art, requires myth. Therefore, the fraught relationship between Ueshiba Morihei and his teacher, Takeda Sokaku alone, quite apart from any technical or psychological innovations, makes this story one of high drama. First is Takeda, a paranoid irascible man, who seems to have lived torn between a need to bond to disciples, one after another, whom he later rejected or more-or-less ignored, having found another. And there is Ueshiba, a man searching for something beyond flesh and blood existence, paradoxically striving find it within the world of violence, like a gnostic striving to liberate the sparks of divinity from the clutches of the muck of the material world. And then they meet: Takeda, sizzling and sparking, wandering throughout Japan like a tengu clipped of his wings, and Ueshiba, craving teachers to mentor him, all the while accumulating social capital amongst terrorists and budoka, military and nobility alike. Takeda was, paradoxically, a free man, self-created, linked to no living teacher nor lineage, yet ensnared within his own paranoid temperament—nothing is lonelier than living behind a wall of spears. Ueshiba was, for much of his life, anything but free--once he found his teachers, Takeda and Deguchi, he was trapped by obligations to two men who tied their followers within feudal rules that they never followed themselves. Takeda, in his own way, loved Ueshiba, the kind of love of a feral cat that will never leave, but will claw your face every time you let your guard down. Did Ueshiba love Takeda? Maybe in the way one loves a crazy girlfriend—she shivers your bones in ways you never imagined, but she tries to run you down with her Pontiac Firebird, all rust spots and primer paint, every time you suggest breaking up.

So, of course they got in a fight about money.

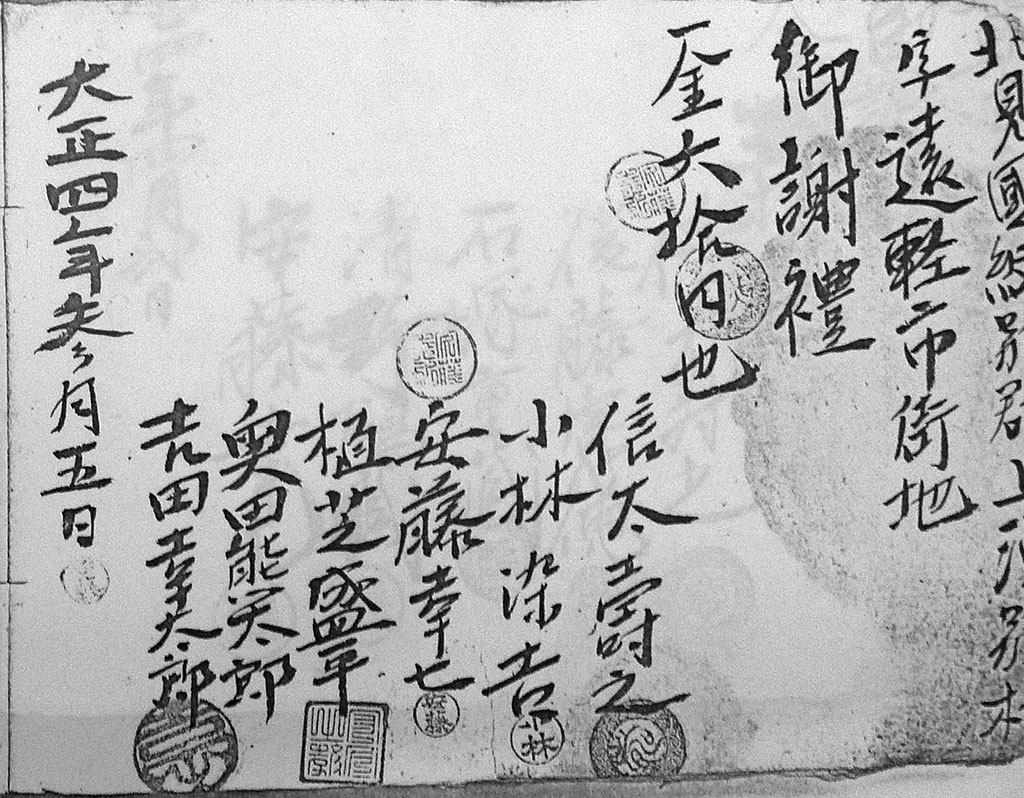

On September 15th, 1922, Takeda Sokaku appointed Ueshiba as kyoju dairi, an assistant instructor’s teaching license, which clearly states, “When instructing students, an initial payment of three yen should be made to Takeda Dai-Sensei as an enrollment fee.” Stanley Pranin wrote about this: “Later each accused the other of improprieties with regard to financial matters, and reports of their last meetings reveal the unresolved nature of the disagreements between them.”

Excerpt from Takeda Sokaku's eimeiroku showing that he appointed Ueshiba Morihei to kyoju dairi on September 15th, 1922. The text referring to monetary arrangements reads as follows: "When instructing students, an initial payment of three yen shall be made to Takeda Dai Sensei as an enrollment fee."

Excerpt from Takeda Sokaku's eimeiroku showing that he appointed Ueshiba Morihei to kyoju dairi on September 15th, 1922. The text referring to monetary arrangements reads as follows: "When instructing students, an initial payment of three yen shall be made to Takeda Dai Sensei as an enrollment fee."

But this fiduciary responsibility was given to anyone who received such a rank. Note the three kyoju dairi entries of Ueshiba Morihei in 1922, Sato Keisuke in 1935 and Nakatsu HeizaburoNakatsu Heizaburo was part of the Osaka Asahi Newspaper security team who studied under Ueshiba Morihei and Takeda Sokaku in the thirties. You can read a biography of Nakatsu Heizaburo here. in 1937. The only distinction is that Sato’s fee was two yen, instead of three.My thanks to Josh Gold for opening up Stanley Pranin's archives and to Guillaume Erard and Christopher Li for extracting those documents and translating them.

Excerpt from Takeda Sokaku's eimeiroku showing that he appointed Sato Ekisuke as kyoju dairi in June 10th, 1935. The text referring to monetary arrangements reads as follows: "When instructing students, an initial payment of two yen shall be made to Takeda Dai Sensei as an enrollment fee."

Excerpt from Takeda Sokaku's eimeiroku showing that he appointed Sato Ekisuke as kyoju dairi in June 10th, 1935. The text referring to monetary arrangements reads as follows: "When instructing students, an initial payment of two yen shall be made to Takeda Dai Sensei as an enrollment fee."  Excerpt from Takeda Sokaku's eimeiroku showing that he appointed Nakatsu Heizaburo, Akune Masayoshi, and Kawazoe Kuniyoshi as kyoju dairi in October 1937. The text referring to monetary arrangements reads as follows: "When instructing students, an initial payment of three yen shall be made to Takeda Dai Sensei as an enrollment fee."

Excerpt from Takeda Sokaku's eimeiroku showing that he appointed Nakatsu Heizaburo, Akune Masayoshi, and Kawazoe Kuniyoshi as kyoju dairi in October 1937. The text referring to monetary arrangements reads as follows: "When instructing students, an initial payment of three yen shall be made to Takeda Dai Sensei as an enrollment fee."

Also note that the handwriting of each certificate was different. Takeda was close to illiterate, and his own students (or a third-party scribe) wrote out each certification. This establishes is that Ueshiba went into this with his eyes wide open—he was not handed a certificate hitherto unseen that he was now obligated to follow.

Stanley told me that he asked an expert on the history of currency about this fee, and he was told that 3 yen was the equivalent of $260. I asked Stanley why there are no known accounts of anyone else having problems with Takeda concerning this exorbitant sum, and he conceded that although other Daito-ryū instructors probably had the same expectation placed upon them, they taught small numbers of students, rigorously selected. Stanley believed that they, surely, selected people who could pay the entry fee. Ueshiba, on the other hand, was teaching huge numbers of people in a variety of settings: the Omoto-kyo’s paramilitary force, public seminars, and at his Kobukan Dojo. As Stanley saw it, it was never formally laid out who was really to be consider a monjin (formal student), so of course there would be trouble between Takeda and Ueshiba.

Were all of the Omoto-kyo disciples as well as everyone who took a seminar from Ueshiba required to submit $260? Consider that if this were the requirement, and were Ueshiba a man of honor, he would personally be obligated to make up the difference for all those students who were not able to pay. This would have been an unbelievable sum – easily going into the hundreds of thousands of dollars. However, the reason this was not "formally laid out" is that, in traditional Japanese arts, the definition of a student and how one became one was already formally understood. It is unimaginable that seminar participants, or those training in the Omoto-kyo militia were considered monjin of Ueshiba’s Daito-ryū (let there be no mistake – that was what Ueshiba was teaching in the 1920’s and 1930’s, and he clearly stated so himself. He himself handed out Daito-ryū certifications to some of his own students in the 1930’s)The book Budo Renshu was often given in place of such certificate but it does bear the mention that it is a Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu certificate. You can read more about Budo Renshu here..

It is true that some Daito-ryū instructors have had a rather shabby practice of claiming that anyone who signed their eimeiroku (registration book) became their student, even if they only attended a one-day seminar, but that’s politics and manipulation, where some time later, the owner of the eimeiroku can brandish that page and say, “See, so-and-so is my student. Here’s his signature.”In It Aint Necessarily So: Banquo’s Ghost, I wrote: “This is something that seems endemic within Daitō-ryū. Horikawa experienced it himself. Because he had already learned some level of Shibukawa-ryū jujutsu from his father, I have read that Takeda Sokaku started teaching him the aspects of Daitō-ryū concerned with aiki, rather than its jujutsu techniques, which were not really all that different from Shibukawa-ryū. Many decades later, Horikawa visited Sagawa Yukiyoshi, another senior student of Takeda, and requested that the latter teach him the jujutsu portion of the Daitō-ryū, over the course of a few days. Sagawa had Horikawa and his accompanying students sign his eimeiroku, and subsequently asserted that Horikawa was, therefore, his student."

In a classical Japanese context, a student is someone who undergoes some type of formal initiation (nyūmon 入門). For example, I have probably had several thousand people participate in martial arts seminars which I have taught over the last three decades, but I have had only a few dozen students in my entire career. It is supposition on my part, but I do believe that both Ueshiba and Takeda would have had a similar understanding on what defined a genuine student, because all Japanese of that period would have understood this. Why would they be different?

In addition, some Daito-ryū instructors did have a fair number of students. Matsuda Toshimi and Hisa TakumaHisa is actually on record saying that Takeda Sokaku did not charge unreasonable amounts of money and that he wasn't interest in such things. immediately come to mind. Even the reclusive Sagawa Yukiyoshi taught dozens and at one point supervised a university club. Yet contrary to Stanley’s assertion, there are no accounts available of Takeda Sokaku having conflict with any of his other students about money. Were all these teachers all rich themselves, specializing in wealthy students? Far from it. How could these teachers—some of them living in rural, impoverished areas, taking adolescents, university students and ordinary working-class individuals as students—pay this debt? In all the many interviews with Takeda Sokaku’s students and successors, not one of them has ever complained of going into debt to pay off what Stanley asserted was $260 per headNote from Ellis Amdur and Guillaume Erard: During a follow-up discussion of this article, we began discussing another statement about Takeda, that he charged money on a technique basis. It is stated as "common knowledge," mostly in articles speaking negatively about Takeda. In fact, Ellis Amdur himself alluded to this claim on page 181 of Hidden in Plain Sight. We have such documents as Takeda's eimeiroku and the shareiroku, where the fee for his seminars are recorded. In fact, neither of us has ever seen a document that establishes that Takeda ever charged per technique. Until such evidence is presented, we regard this as yet another unsubstantiated statement about Takeda’s, which is often used as an attack on his character..

Most important, however, was Stanley even correct in his assertion that the entrance fee was so expensive? Stanley and I had a warm, collegial relationship. He was a meticulous researcher, while I tended to be quite iconoclastic, yet he was always interested in my viewpoints and would revise his opinions, on occasion, after giving thoughtful consideration of my ideas. With one exception: once Stanley heard from someone that three yen was so expensive, he never researched it again, and in fact, was resistant (as resistant to any concept as I ever found him) that the exchange rate might have been different.

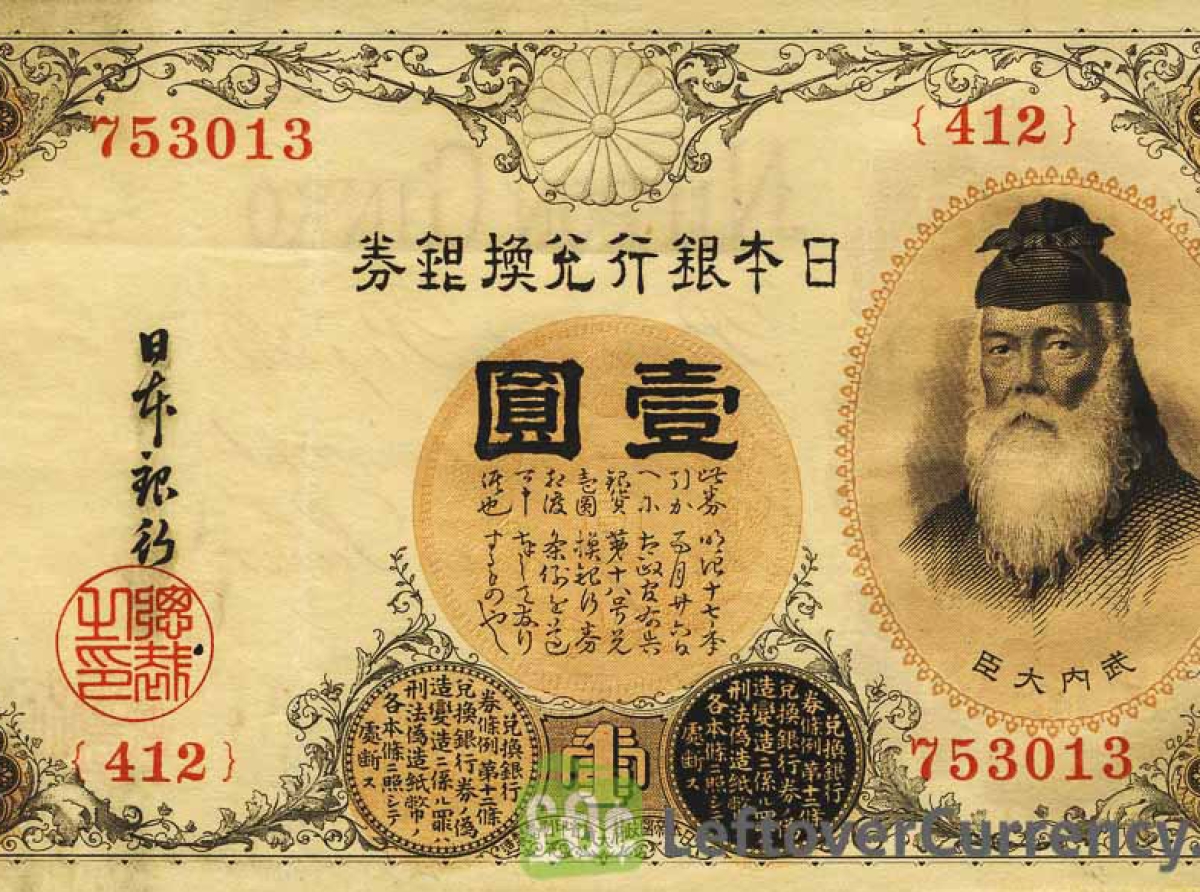

There are a number of measurements of value, a quite complex subject, particularly when it concerns the exchange rate between currencies, and the cost of living in different era. To understand the value of 3 yen in 1922, I have chosen to use “absolute buying power” as a metric. Let’s start with a few facts:

- According to the official exchange rate, three yen was regarded as equal to $1.50

- As we see here, three yen is worth approximately $22 in 2018 money.

For another take, according to the Historical Statistics website, three yen in 1922 could buy the same amount of consumer goods and services in Sweden as $16.53 in 2015.

We could be more meticulous, but it is pretty clear that three yen in 1922 would have the buying power of $19-20 today. So what could Takeda buy today with that?

- Three cocktails at a dive bar on Hotel Street in Honolulu

- Four ½ liter containers of Talenti Sicilian Pistachio Gelato

- One three - four minute lap dance in the main room of a strip club in Pottstown, Pennsylvania

- Six kilograms of koshihikari rice

- One or two fundoshi on eBay

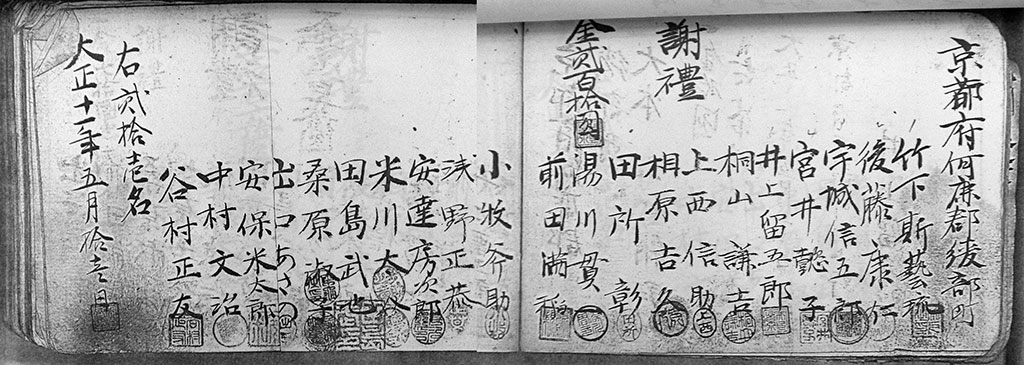

Another marker of the value of money in Takeda Sokaku’s and Ueshiba Morihei’s eyes is seminar fees. Here, below, are two shareiroku: enrollment sheets of seminars presented by Takeda Sokaku. The one on the top enumerates six people (including Ueshiba Morihei) for a total price of 60 yen, and the one on the bottom enumerates 21 people for 210 yenMy thanks again to Josh Gold, Guillaume Erard and Christopher Li..

Excerpt from Takeda Sokaku's shareiroku for the 5th of March 1915. It says that six persons, including Ueshiba Morihei, trained in Hokkaido and that the group paid 60 yen, hence making the fee 10 yen per head.

Excerpt from Takeda Sokaku's shareiroku for the 5th of March 1915. It says that six persons, including Ueshiba Morihei, trained in Hokkaido and that the group paid 60 yen, hence making the fee 10 yen per head. Excerpt from Takeda Sokaku's shareiroku for the 11th of May 1922. It says that 21 persons trained in Ayabe and that the group paid 210 yen, hence making the fee 10 yen per head.

Excerpt from Takeda Sokaku's shareiroku for the 11th of May 1922. It says that 21 persons trained in Ayabe and that the group paid 210 yen, hence making the fee 10 yen per head.

According to Stanley Pranin’s original figures, this would be quite exorbitant, about $870 per person. The second seminar, then, would have cleared over $18,000! At the rate described above, this would be $55 a head for a multi-day seminar. Quite reasonable, really—far more so than most martial arts seminars today.

How much did Ueshiba charge his students? In Mr. Kimura’s Aikido Memories, concerning his training in the 1930’s, he states: “The monthly tuition was 5 yen. We would be scolded if we just handed over a 5 yen note in the open. We’d always place it in a an envelope (noshibukuro / 熨斗袋) and one of the uchi-deshi would place it on top of the sanpo (三宝, a small stand). Then the uchi-deshi would raise it above their eyes and place it reverently before the altar.” (True, Kimura trained in the next decade. But Takeda did not adjust his kyoju dairi for inflation or deflation either). In fact, in 1934, the yen had lost considerable value in the 1930s - five yen was worth a mere $21 dollars.

The implications of this are, in my view, huge. By registering Ueshiba Morihei as kyoju dairi, Takeda Sokaku certified him as a legitimate instructor, essentially opening up an entire world of opportunities for him. In return, Takeda expected continued respect, and the commitment to engage in continued education (hence his visits to Ueshiba throughout the 1920’s and half of the 1930’s), but in addition, Ueshiba was expected to offer a mere pittance, a one-time payment that was kind of a token of gratitude and recognition, rather than a source of Takeda’s income.

In one story, the myth, Takeda ensnared Ueshiba in an inescapable dilemma. He demanded a fee per student that few could afford. If Ueshiba were to teach anyone other than rich people, he would have to make up the difference himself, very likely impoverishing his family. Yet, Ueshiba was undeniably teaching Daito-ryū, all of which he owed to Takeda Sokaku. According to the myth: He Had To Pay – He Couldn’t Pay. Ueshiba was trapped, wanting to offer something powerful, transformational, to the world, yet he was enmeshed within a debt he could never get out from under. So goes the story.

Or, Takeda asked for what appears to be a small sum, a mere intellectual property fee for the instruction that enabled his kyoju dairi to feed their own families, to rise in social status and contribute to their society. Thanks to Takeda, Ueshiba Morihei was teaching generals and admirals, the paramilitary of a religious cult, the nobility, even the Imperial family, but he didn’t pay his teacher the pittance he promised: either he stopped at a certain point, or he never paid at all.

In the end, I’m sure that there is much unsaid, unwritten and misunderstood, the truth in such conflicts truly lying in the shadows between two such individuals. Nonetheless, I believe Takeda Sokaku was unfairly described in the ‘standard myth,’ and his bitterness towards his student more justified that the aikido origin story would have it.