As my work is receiving more attention from the aikido community, I am sometimes getting questions from some of my readers regarding the fact that my interviews and documentaries seem to revolve essentially around the Aikikai. Notwithstanding my work on Daito-ryu aiki-jujutsu, this over representation is of course quite true, but it is not necessarily the product of a choice. Indeed, being a student of the Aikikai Hombu Dojo, most of my close connections belong to that group. However, as a historian of aikido, I do have an interest for all legitimate currents issued from the teachings of Ueshiba Morihei. Among the many people who challenge the representation biases in my work, very few ever propose to help me alleviate it. One of them is a Canadian budo practitioner living in Japan called Reg Sakamoto. We had a short conversation via social networks and he quickly offered to connect me with his own teacher, a prominent instructor from the Yoshinkan. I jumped on the occasion and a few weeks later, I was in Kyoto meeting him and his teacher, Jacques Payet, who was an uchi deshi of the great Shioda Gozo. Jacques Payet is a long term resident of Japan and he runs his own school, the Aikido Mugenjuku in Kyoto.

Guillaume Erard: As a start, could you tell us where and how you started your martial arts practice?

Jacques Payet: Since I was a kid, I've always been drawn to martial arts, probably due to the influence of Bruce Lee. But as I was on La Réunion Island, there were only a few judo practitioners, and the dojo was quite far so it was practically impossible to find a teacher.

After I left La Réunion, I spent maybe four or five years in Lyon for my studies and it’s from that point that I started. I started with kung fu, then I did a little Shotokan karate, and then I started ju-jutsu. One day, I saw an 8mm film of Shioda Gozo, a little man who threw people much larger than him while laughing. I thought that it looked like magic and that I'd love to go see this if that was real. That's how at age 22, without knowing anything about Japan, without knowing anyone there, I decided in all my youth, out of pure madness, to come to Japan and meet Shioda Sensei.

Guillaume Erard: You hadn't practiced aikido in France?

Jacques Payet: No. Besides, I had a pretty negative image of aikido, it was too weak, it wasn't manly enough. I particularly wanted to do ju-jutsu, there is a lot of virility in there, and I saw aikido as too soft. When I saw that film in Japanese, I didn't realize it was aikido, I thought it was ju-jutsu, so I came here looking for: “Shioda Gozo, professor of ju-jutsu" so obviously everyone was surprised. It’s after that I understood of course that it was aikido, and that it was Yoshinkan. So I think that if Shioda Sensei had done karate or something else, today I would be practicing that today.

Guillaume Erard: When I looked at your biography, I was was indeed surprised by the fact that you went straight to Shioda Sensei, when anyone else would have said: "Shioda Sensei is very good, he does aikido, I'm going to do aikido."

Jacques Payet: Yes, I came for Shioda Sensei, and so I really entered through the small door.

Guillaume Erard: I guess by "the small door", you mean, without any introduction...

Jacques Payet: Right, nothing at all. And besides, it was 1980, so there was no internet, there was nothing, and since I spoke very little English, I had very little information at my disposal. I just had that name.

When I was in Lyon I had made the acquaintance of Japanese student and we had become friends, so when I arrived, I called her and I said: "You have to help me find this teacher, he does ju-jutsu, we have to find him." So it was her who assisted me, we visited almost all of the dojo in Tokyo, and then finally we went to Omiya in a koryu dojo, and the teacher there told us: “I know Shioda Sensei, his dojo is in Koganei." Then we looked in the phone book, we called, and that's how I joined the dojo.

Jacques Payet in the entrance of the Koganei Dojo (1983)

Jacques Payet in the entrance of the Koganei Dojo (1983)

Guillaume Erard: Considering the time, Tokyo was probably very different from today. How did your arrival go?

Jacques Payet: It was quite chaotic, I had very little money so I posted an ad. I was at the University of Tokyo in the French literature department and I put an ad in French: "Young student would like to share accommodation with a Japanese." I got an answer two days later I think, but it was quite far, in Saitama. I shared the apartment with him. Around 2 p.m., I would take a two-hour ride by train to Koganei so that I could attend the beginner classes from 4 to 8 p.m.

After a month, all my savings were gone, and so on the last day I said goodbye to everyone. I went to the dojo to say that I was really sorry, but that I had to leave because I had no more money. By chance, in the parking lot, there stood the son of Shioda Gozo. He was planing to go to England to teach, and he was looking for foreigners to talk to in English, so he was very excited to speak with a French person. The two of us did not master the language well, but with a few words we could understand each other, and so I explained my situation and he said to me: "Well, today must be your lucky day because my father is here, so if you want I can introduce you." I told him that I had come to Japan precisely to meet his father but that after a month there, I had not even seen him, so it would be a shame if I had done this whole trip and left without having seen him. So he said to me, "OK, no problem" and he took me straight to Shioda Gozo's office, and he explained my situation to him.

Jacques Payet in Shioda Gozo's office (1982)

Jacques Payet in Shioda Gozo's office (1982)

After a while, Shioda, who was very small, stood up, he looked at me right in the eyes and said: "Is it true that you came on purpose to do of Aikido and that you would like to stay?" I told him of course, and he told me: "OK, if you're courageous, if you can get up early in the morning, do all the chores and in addition, if you can do 6 hours of lessons per day, then you are welcome to stay in the dojo, you have nothing to pay, or very little, just for amenities, water, electricity, stuff like that. If you're interested you can stay 3 months, and if I think you deserve it we'll see after that."

I was amazed, I thanked him and said that I accepted immediately. That's how all of a sudden, my life changed completely. The next day I moved into the dojo.

The sleeping area for the uchi deshi (1983)

The sleeping area for the uchi deshi (1983)

Guillaume Erard: This is something I heard from Kobayashi Kiyohiro, one of my teachers in Daito-ryu, who trained at the Yoshinkan for a while in the 1960s. When I asked him if he had taken a lot of lessons with Shioda Sensei, he said: "No, he was too important already, we couldn't take lessons with him just like that." Did he teach regularly, or were there private lessons?

Jacques Payet: My first time in Yoshinkan was, I believe, in October 1, 1981. At that time, he was doing regular classes in the evening, I think it was Tuesday evening for an hour, and Friday, or something like that. Otherwise he only did black belt courses, or special courses, maybe twice a week, and the rest of the classes were done by his instructors. He just walked around.

For example, I did not take really ukemi for him until... You had to be at least shodan, before that, you couldn't take ukemi for him. He didn't speak to me at all for a year. If he saw anything that I was doing wrong, he would go to the teachers and ask them to correct me. There was no direct contact. So I had to wait for when I became uchi deshi, when I took care of him. I can't say that I could talk to him freely then, but there was some communication, and I took ukemi for him.

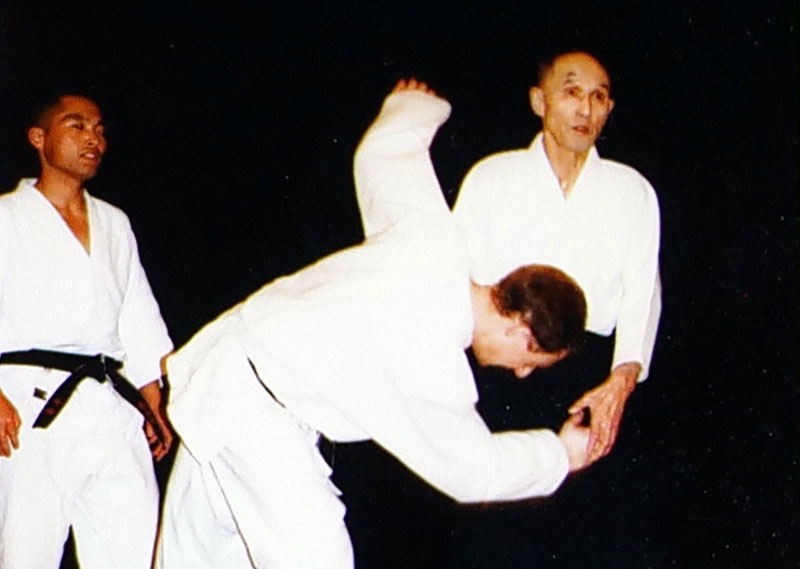

Jacques Payet and Ando Tsuneo taking ukemi for Shioda Gozo (1990)

Jacques Payet and Ando Tsuneo taking ukemi for Shioda Gozo (1990)

Guillaume Erard: There is debate, even in Japan, about the current meaning of the term uchi deshi. In this case, there was a direct relationship, you were uchi deshi of Shioda Gozo, not just a resident student at the Yoshinkan.

Jacques Payet: That's right. I think I was lucky because I was included in this small uchi deshi group, in the sense that a lot of training was done outside of the tatami so it was really still the traditional teaching. What shocked me was that there was the corridor, there was the office where all the instructors and deshi were, there was Shioda Sensei's office next door, and there were two doors, one here, and a one here. Part of the training was to feel when Shioda Sensei was going to come out of his office, but since there were 2 doors, we didn't know from which one. The training was to guess... It depends, maybe we were chatting or drinking, and with the sound of the door opening, we knew immediately which door it was and we started to open the bathroom door, etc. There was a sense of timing and not thinking, that the body react automatically.

Jacques Payet in the staff office at the Koganei Hombu Dojo (1982)

Jacques Payet in the staff office at the Koganei Hombu Dojo (1982)

That was the teaching of uchi deshi. There was all this non-verbal aspect that was there and that was becoming almost automatic, and the body was moving on its own, practically. It was not conscious but it brought me a lot. After a while, it became an extraordinary asset that I used in the technique on the tatami. Then, it's the same for the bath, for example. It's only bathing, but it's so Japanese, in the sense that there are no words, it is communication by osmosis. You have to be there at the right time. You can't hesitate, you have to be there. You have to learn from heart to heart, or body to heart, it's a truly unique teaching, and I think that's what maybe is missing today. Without it, I think my outlook on aikido would have been completely different.

Guillaume Erard: On this subject of the ishin-denshin relationship...

Jacques Payet: Right, that's what it is.

Guillaume Erard: The last person I spoke to who experienced this, other than you, and it was in the completely different domain of rakugo [storytelling], was Katsura Sunshine, who lived with his master exactly in that way. The question we asked ourselves was that indeed, if we want to learn an art thoroughly, it's quite difficult in the Japanese system to do it differently from that, and it is not accessible to everyone, necessarily, and by design. Is this system it still continuing or is it in decline?

Jacques Payet: I personally think it's in decline. Because not too long ago I was at a sushi place, and the guy told me that now, to open a sushi store, you just have to go and take lessons in a school for a year or two, and then you get a qualification. And so it's no longer necessary to be an uchi deshi, to clean for a year or two before you can touch the knife and do the thing... Everything is done in a modern way. I even see it in the Yoshinkan, the system no longer exists. I don't know in other arts, how is it's going, but I think it is in decline and I also think that young Japanese people are not at all interested anymore. I don't think they intend to spend four or five years just staring or cleaning, they immediately want to take action and to learn.

Guillaume Erard: I see. Without having been to such an extent of close long-term relationship with my own Daito-ryu teacher, the late Chiba Tsugutaka, it is true that I can't see how certain things, certain teachings that I received from him, could have passed otherwise.

Jacques Payet: Right.

Guillaume Erard: Without even being able to explain it, actually.

Jacques Payet: Exactly, right. Because I remember things, mundane things, for example, Shioda called us to bring him a nail clipper. So we brought him a nail clipper and then we looked, we waited for him to cut his nails, and then, as if by chance, he said to us: “Here, what I have here, it's so hard that it's difficult for me to cut my nails. " So it was a way for him to explain that this is where you have to put your balance...

Guillaume Erard: You body weight...

Jacques Payet: Right, where you put on the weight on, lean on, and so if we happened to have something elsewhere, that meant we did it wrong. It is an indirect way of teaching but if it hadn't been for that opportunity, I wouldn't have known that it was the important point, because nobody would have said it. So there are a lot of times like that where you have to be there right now, otherwise, you won't know.

Guillaume Erard: And the meaning does not necessarily reveal itself immediately...

Jacques Payet: That's right.

Guillaume Erard: I imagine that you are still thinking about those things…

Jacques Payet: Yes, years later: “Ah, that's what he meant back then." That is something I would like to pass on to my students but it is difficult.

Guillaume Erard: And the system is dying little by little for lack of will from the students to invest themselves in this type of long-term relationship, and in particular if there are faster parallel ways, of course, which we can see a lot anyway - maybe less so in japan - but in any case in the rest of the world, a professionalization of aikido...

Jacques Payet: There you have it.

Guillaume Erard: To be competitive, you have to do seminars, you have to get grades, and who has time to spend 10 years, completely unknown, in the shadows?

Jacques Payet: Quite so. It's a shame but maybe it's the time that wants it.

Guillaume Erard: How do you manage to overcome this pedagogical lack in your own teaching?

Jacques Payet: That's why I wanted to create a little more specialized classes, and therefore I set up the kenshusei, with the condition of living in community. We have a house and the kenshusei are forced to stay for a year and live together. So it's not a hotel, they have to really take care of it like a dojo. And besides, I try to keep - well it doesn't go as far as an uchi deshi - but I still try to keep what was important to me, such as respect and attitude towards seniors. To surpass oneself, of course physically, but also mentally. I try to do the whole lot, but it gets harder and harder, because for young people today, It's difficult, they can't stand it. I think two years ago, I had two young people in their twenties, they didn't last a week... They were mostly in shock... They'd never seen that so...

Guillaume Erard: There is certainly an image problem with this, because I regularly receive emails asking me: I really want to become an uchi deshi, where can I be an uchi deshi? And I respond: "Do you understand what it is?"

Jacques Payet: Right.

Guillaume Erard: Are you ready to give up everything, without really any resources.

Jacques Payet: Right. Because it's an almost total sacrifice, it's practically becoming someone's slave.

Guillaume Erard: That's it, and without guarantees. It's not like a university degree where it ensures you an income afterwards...

Jacques Payet: Right, there are really no guarantees.

Guillaume Erard: To get back to the uchi deshi group of the time, how many people are we talking about, and were there already foreigners?

Jacques Payet: Yes when I arrived there was a Frenchman, Jacques Muguruza, who also stayed for five years and I believe that before him there was someone from New Zealand who stayed for a year. And before that I think there was a Korean, but that's about all. Muguruza left after a year and so I was alone, I was the only foreigner.

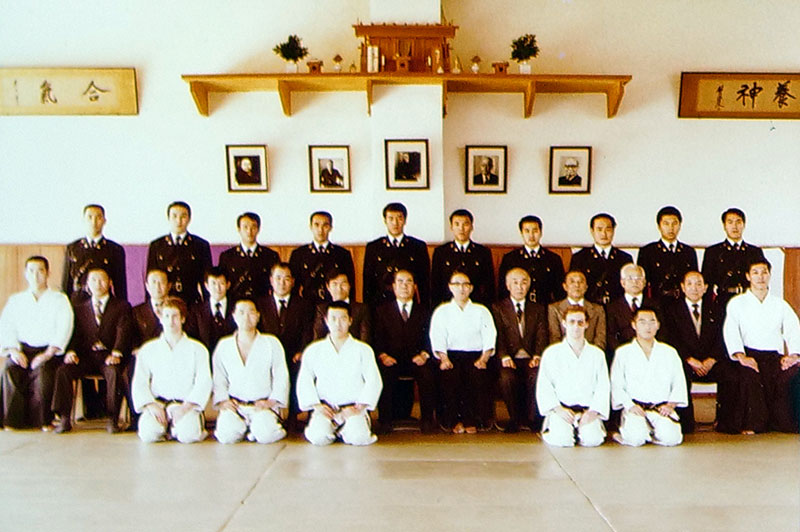

The uchi deshi in front of the Koganei Dojo (1983)

The uchi deshi in front of the Koganei Dojo (1983)

Guillaume Erard: Once you enter the uchi deshi system, after a certain period of time are you given teaching responsibilities in the organization?

Jacques Payet: Yes, because when I got here so I started at 1980... in 1981, i became uchi deshi, and therefore in 1982 -83, as there were starting to be more foreigners who came to Japan to train at the dojo, they put me in charge. - I think it's also because they didn't want to... it was easier for me to take care of it... - So my role was to teach beginners and especially foreigners, and after a while, it was foreigners and Japanese at the same time, so I took care of beginners like that. So I was an assistant instructor and then later I became an instructor.

Guillaume Erard: But I imagine that there are also other systems of instructors in place, outside of the uchi deshi program itself?

Jacques Payet: When I was in Yoshinkan, no, you had to be an uchi deshi. It was done internally. There were no people from outside who could become instructors.

Guillaume Erard: An obvious difference compared to the functioning of the Aikikai, which I know a little better, is that there have been foreigners in the teaching staff of the Yoshinkan for a long time.

Jacques Payet: Yes.

Guillaume Erard: And it's still not the case at the Aikikai. Do you know how it came to be at the Yoshinkan and what was the idea behind it?

Jacques Payet: I think it all comes from the relationship with Shioda Sensei. I don't remember his name, but there was an Englishman who was a student in the 1950s, at the beginning. He was very close to Shioda Sensei, and since he was well off, I believe that when he returned to England he gave him his house. So the house where Shioda Sensei lived until his death belonged to one of his students, he gave it to him, it was like that, because he respected him. I think that it influenced Shioda a lot.

Since that, there has always been a good relationship, he was very open-minded. The uchi deshi who were there, whether it was the New Zealander or the Frenchman Jacques Muguruza, they really loved aikido, they had done their best, so i think he had some respect for that. So that's wh he was openy, I think. That's what made the difference I guess.

Guillaume Erard: Once these uchi deshi returned to their countries, what happened? Was there still some kind of continuous contact with the Yoshinkan? I'm thinking for example of the terms of curriculum or exam criteria, things like that, or did everyone do their own thing?

Jacques Payet: No, it was still... It's a little different since they created the Yoshinkan InternationalThe International Yoshinkan Aikido Federation (IYAF) was created in 1990 by Shioda Gozo to facilitate the learning of Yoshinkan aikido outside Japan., but before it was only a direct line, it was Shioda Sensei, there was only one curriculum, and all the deshi followed that to the letter. So initially there were very few branches, really. The first one was setup by one of the oldest uchi deshi, Kushida Sensei. In 1973 I believe, he went to Michigan in the United States, and it is he who really developed the Yoshinkan in the United States. And so there was the shibucho, and it is the shibucho that recommended the students directly to Japan, so there was a system of trust. They really followed the Hombu curriculum, until almost 1990, when they setup the International Yoshinkan Federation. From that time, everyone did a little bit as they wanted, so we lost a bit of this very strong relationship between the Hombu and the foreigners.

Guillaume Erard: Going back to Shioda Yasuhisa, it's thanks to him that you could enter the Yoshinkan. You are roughly of the same generation...

Jacques Payet: Yes, I think that he's two or three years older than me.

Guillaume Erard: Did you have a special relationship due to this age proximity?

Jacques Payet: Yes, because I think that he was under tremendous pressure from his father. There were a lot of expectations for the son to be as good as his father. I don't think he couldn't really handle that pressure, so he felt a little isolated, and due to the fact that he was never really an uchi deshi, he didn't get along that well with the uchi deshi. He felt like he was in competition, so he felt a bit lonely and sidelined. So I think that it was easier for him to speak to a foreigner. I think that it had an influence.

Guillaume Erard: It's interesting because when we look at the way the Aikikai functions, with the successive generations of Doshu, in the Yoshinkan, we're also in a system from father to son, a pseudo iemoto, even though I don't think that O Sensei ever referred to aikido as an iemoto system. Nevertheless, a number of his students afterwards have established those lineages, whether it is Saito Sensei with his son, at the Aikikai with the Doshu, or at the Yoshinkan. Is it a Japanese custom that came back?

Jacques Payet: I think that it's a custom, because I'm sure that Shioda Sensei would have wanted his son to succeed him. Towards the end of his life, he confessed to me that he was a bit sad about the fact that everyone, from the uchi deshi to the members of the federation, were against that idea. That's why they appointed Inoue Sensei as kancho.

Guillaume Erard: Precisely, because juridically speaking, the Yoshinkan is a hojin, so there is a whole pseudo-democratic system associated to it. I guess that we can draw a parallel with our association system in France, so people are elected, they're not appointed unilaterally.

Jacques Payet: No, there needs to be a consensus.

Guillaume Erard: It didn't happen like that at the Yoshinkan?

Jacques Payet: There were many problems between the top shihan, at the beginning, but then eventually reached a consensus. They said: "Let's put Inoue Sensei there for a few years, and after, Shioda [Yasuhisa] Sensei can take over." It was setup like that, in the secret hope that those few years would last a long time... [laughs] But Shioda [Yasuhisa] Sensei didn't agree at all with that, so he setup a Coup d'Etat in the system after three years, so Inoue Sensei got sacked, and it's him who became kancho. But three years later, there was another problem and it's him who got kicked out. Nowadays, there isn't a kanchoKancho (館長): director , instead they put a young guy as dojo-cho, with a committee of the highest ranked shihan, who take the most important decisions such as the high rank promotions, etc. The current dojo-cho takes care of the day-to-day business.

Guillaume Erard: As regards to the organization itself, it's a lot of trouble in a very little time, and I guess that it led to splits into different groups. How did it translate in terms of the size of the Yoshinkan, domestically in particular?

Jacques Payet: It really got segmented. Now there is the Yoshinkan, which is really small...

Guillaume Erard: By that you mean the Yoshinkan Honbu Dojo in Tokyo?

Jacques Payet: Yes, the Honbu Dojo. I don't know how many members there are left, and with the Coronavirus, it must be even worse. When the shihan decided to leave, about half of the students followed Chida Sensei. After that, Takeno Sensei left as well, then Inoue Sensei, then Ando Sensei created his own organization... They all went their separated way, they didn't gather... Both. Chida Sensei and Inoue Sensei completely separated from the Yoshinkan, and they created their own organizations. They have nothing to do with the Yoshinkan, even though the techniques and everything else is the same, but still... Ando Sensei created his own separate group, while keeping some contacts with the Yoshinkan. As of now, it's him who has the largest organization. It's a real shame and that's precisely what we regretted last time, in the interview in did with Thambu SenseiYou can watch the discussion between Jacques Payet and Joe Thambu here. We regretted the fact that now there are egos and everybody wants to be king of their own kingdom, and that there is no longer any spirit from the old Yoshinkan, where everybody was working and training together.

Guillaume Erard: While on the subject, we see that Thambu Sensei, who went with Inoue Sensei, still talks with you, Mustard Sensei, and several others that I could see in his interviews. Once those splits happen, do the foreigners have a more collaborative attitude, or not?

Jacques Payet: I would like to say yes, but I'm not sure. [laughs] It's the same thing, many foreigners are professionals, so even if they might like to cooperate, often, for financial reasons it's important to have one's own group and to be quite selfish. It's a pity but it's like that. As regards to Thambu, Mustard, etc. those people are friends. We trained together, so there are bounds of friendship that remain. That's why we are still together even though we belong to different organizations.

Guillaume Erard: So you still give seminars together from time to time?

Jacques Payet: Yes, not regularly but in September last year, they invited me so of course, I participated in the seminar. The ideal of Thambu and Mustard is to gather all the senior Yoshinkan members, so we can at least work together from time to time. I think it's a very good idea.

Guillaume Erard: What is your position, as an individual and as an organization, relative to the Yoshinkan Hombu Dojo in Tokyo?

Jacques Payet: First, I understand that for them, the situation is difficult. They are young and they have to deal with shihan who have much more experience, who have been uchi deshi while they have not, and their role is to be above and get everybody to agree. That's a very difficult thing to do. That's why I try not to be too critical and if they ask me to help, I advise them, and I'm very happy to do what I can. I think it's important to have a Hombu. I regret that the name Shioda is no longer in the organization. Now for instance, the grades are signed by someone that I had never met personally. That's a bit sad.

Guillaume Erard: Do your students' grades still come from the Honbu?

Jacques Payet: Yes, they do. It's my way to thank Shioda Sensei, to stay in his organization. Because everything I have is thanks to him so this lineage, even if it's at that level, is important.

Guillaume Erard: It's interesting because the question is always whether we are faithful to the Emperor, or to the Empire.

Jacques Payet: That's it!

Guillaume Erard: I think that I am not misrepresenting the views of many people at the Aikikai when I say that that there is a fidelity to the Ueshiba family, I think. The reasons are very diverse of course. It seems that there is less of that in the Yoshinkan.

Members of the Aikikai Hombu Dojo with the Ueshiba family at the Aiki-taisai in Iwama.

Members of the Aikikai Hombu Dojo with the Ueshiba family at the Aiki-taisai in Iwama.

Jacques Payet: Yes, I think so. For those who stay in within the Yoshinkan, I think that there is this emotional attachment. The Yoshinkan was really a small organization. There was only Shioda Kancho at the center. He had a very open personality, he enjoyed drinking with everyone and making jokes , he knew everybody. He was very simple with everybody, he wanted to know everything. So at least for the seniors, there is something that remains, something that they want to keep.

Guillaume Erard: You now live in Kyoto, you opened a dojo in Kyoto. Everyone knows that in Japan, things are not always easy for a foreigner, but the image of Kyoto for someone like me who only knows Tokyo, for instance, it seems to me even more difficult. [laughs] Is it the case? Did you have any particular difficulty to set yourself up?

Jacques Payet: Strangely no, not really. On the contrary, I think that being a foreigner might have made things easier for me because people were a little surprised at first, but they realized that coming here was an opportunity to meet foreigners, to communicate, share different cultures... And then I try to make them feel comfortable, women... So at the beginning, they were a little curious, but after that, through reputation, it went very well, I think. As for me, since I'm far from Tokyo, I'm sheltered from all politics. I can just focus on training and it is very good like that.

Guillaume Erard: So senior people like you do not have a technical role at the Honbu Dojo?

Jacques Payet: For the first 2 or 3 years, they asked me to come to the dojo once per month so I had my own monthly class. Sometimes I also taught the police. But that ended up being quite expensive, so it stopped. Then sometimes, especially when there is a problem with a dojo abroad, they call me and ask for my opinion. Because I'm the sempai, I have a lot of freedom.

Guillaume Erard: I'm probably wrong about that, but regarding the image I had of the Yoshinkan relative to that of the Aikikai in Japan, in terms of organizations, I was under the the impression that they were about equivalent in size.

Jacques Payet: No, the Aikikai is much larger. I don't want to say something inaccurate but in its prime, the Yoshinkan had perhaps 2000 members in Japan.

Guillaume Erard: It's interesting because in terms of media presence, the relationship is completely disproportionate. Shioda Sensei did a lot of work to promote Aikido after the war.

Jacques Payet: Yes, but he was mainly in the police and in the army, but in the public for example, there are very few university clubs. The Aikikai did a fantastic job on that.

Guillaume Erard: Tomiki too.

Jacques Payet: Yes, while there are very few [Yoshinkan] university clubs in Japan. It makes a big difference.At the Yoshinkan, the focus of Shioda Sensei was on quality, to do something really solid. That's what was important, this spirit, the yoshin: "spirit". That's always been there, very strong. So it wasn't important if there weren't many students. In any case, there were sponsors, so that didn't really matter.

Guillaume Erard: You mentioned the police. The Yoshinkan is very famous for his program for the police, which was also attended by the uchi deshi. I think that most people who'll read this interview — me included — learned about this program through the book: "Angry White Pyjamas". You are actually mentioned in the book. Is the representation made in the book accurate?

Jacques Payet: Yes I think so. Of course, it's a little exaggerated in order to make it a compelling story, it's normal. But I think that it's about right. When I created my kenshusei course here, I wanted to get rid of those negative aspects because that's something that would no be acceptable anymore today.

Guillaume Erard: We see that in sumo too...

Jacques Payet: That's right.

Guillaume Erard: You'd think that in sumo, one signs up for that sort of abuse, but it does make headlines these days. In judo too.

Jacques Payet: When I took part in the senshusei, there were explanations: "For shihonage, do like this, and like that", but the leitmotiv, what was really taught was to hit the head on the floor, on the tatami. If we didn't smash the guy's head in the mat, our shihonage wasn't good. [laughs] Hour after hour, every day, "bam! bam!" it's terrible. There were even some accidents.

Guillaume Erard: I think that shihonage is one of the most accident-prone techniques.

Jacques Payet: It was common.

Guillaume Erard: I wasn't at the Aikikai at that time, so I don't know what went on there, but what surprised me when I started Daito-ryu is that I expected that sort of things, but it wasn't the case. It happens at times, but it's a question of relationship between people, it isn't systematic. So this rather brutal approach, — perhaps it's not the right word — it came from Shioda Sensei, since it was his organization.

Jacques Payet: Yes. I supposed that Ueshiba Sensei's "Hell dojo"...

Guillaume Erard: The Kobukan...

Jacques Payet: Yes... It was like that. But here, it was for the policemen and the uchi deshi only.

Guillaume Erard: For those who signed up for that.

Jacques Payet: Yes, for those who signed up. It stayed within that small club.

Guillaume Erard: To get back to the police, there are also certain things that might need to be clarified. Most policemen are more or less obliged to do one or several budo, kendo, judo, karate, aikido... Since the end of the war, the police has had its own form of defense aimed at being applied in the street, which is the taiho-jutsu. So what is the place of budo, and in particular aikido, in the police training?

Jacques Payet: Shioda Sensei went directly to several police stations and he worked with kendoka, judoka, etc. and apparently, they were impressed and thought that aikido might be useful. But I think that it is mainly the mental aspect. To have a strong determination and to foster a strong character for the policemen. It was based on that mainly. And also because especially in Japan, you can't strike someone when you arrest them, so things like nikyo are more practical and easier. But it's essentially the training of the spirit.

Guillaume Erard: Just like being hit repeatedly with a shinai in kendo is supposed to build character...

Jacques Payet: Right. Especially since they worked with the uchi deshi, etc. if they could have their head smashed on the floor for a year but still be in shape afterwards, they would probably be better officers.

Formal graduation of the 17th police senshusei (December 1981)

Formal graduation of the 17th police senshusei (December 1981)

Guillaume Erard: So it was more a conditioning of the body and the spirit.

Jacques Payet: Yes, the spirit.

Guillaume Erard: I'm going to give you a figure that I foundJordy Delage - Kanto Police Department’s Yoshinkan Aikido Demonstration / Competition, I don't know if it's true at all, correct me if I'm wrong. It seems to me that today in the Tokyo police, 90% of the aikidoka are women.

Guillaume Erard teaching a group of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police (2010)

Guillaume Erard teaching a group of the Tokyo Metropolitan Police (2010)

Jacques Payet: Yes, yes.

Guillaume Erard: Did it affect the kenshusei program for the police?

Jacques Payet: Enormously. Since about 10 years ago, it has been impossible to work in the same conditions as before. I remember that before, for example, that the strike at the end of shihonage the goal was to know from which amount of power did the arm break. [laughs] They did it 10 times and I remember, at each class, there were at least three people who had a double fracture. By just blocking like that. But it was completely normal, nobody was going to complain because if the policeman complained, he lost his job. So they really didn't want to complain, they got a cast setup and they smiled. They would suck it up. Today, you would end up in court and there would be a huge problem.

Also, before, it was voluntary, but it was a kind of forced volunteering. "You, you're 3rd dan in kendo, go and do that course." "Osu". Today it's not like this. "Sorry I have a family life..." So it's very hard to find volunteers. So today, I think that more than half are women in the kenshusei, and it's harder and harder to find volunteers. The program is also a lot softer. They have to be careful, there are a lot of things that they can no longer do.

Guillaume Erard: But do you think that the police, as a force, lost as a result in their ability to do their work?

Jacques Payet: I don't know. I think that they still draw a positive experience out of that. For the character, it's still a very good thing.

Guillaume Erard: It still is no walk in the park.

Jacques Payet: No it's not, but it's not what it once was.

Guillaume Erard: Thambu Sensei asked you this question, but I'm going to ask it to you in slightly different terms. Relative to the practical aspect of aikido, that is, in the street, Thambu Sensei said, and he's right, that the Aikikai did not put the practical consideration at the forefront of its conception of aikido. Do you think that the Yoshinkan, as an organization, — now based on the discussion we had earlier, it might be difficult to answer, so let's talk instead about the idea that we have of the Yoshinkan — is street efficacy a fundamental concern of the practice, and if that's the case, what are the differences? Or is there room left to interpretation?

Jacques Payet: I'd say that the practical and self-defense applications were quite important 20 or 30 years ago. But today, I don't see much of a difference between the Aikikai and the Yoshinkan. Certainly not in Japan, because the practical aspect is not studied or taught at all.

Guillaume Erard: It's the ningen keisei...

Jacques Payet: Right. And people are customers. [laughs] They need to enjoy themselves. But it depends on the countries. For instance, when I go to Ukraine, it has to be practical, it has to be applicable. But whether we are Aikikai or Yoshinkan, if we have strong basics, it's very easy to apply. You just have to change a bit, adding the elbow or the knee, adding a punch while doing shihonage or kotegaeshi, it's easy to turn that into self-defense.

Guillaume Erard: It's a question of perception and having a conditioned body...

Jacques Payet: When we're solid, it's easy to adapt. Then it depends on the character and personality of the teacher. Some people like Reg Sakamoto like that, and that's good. Some are a little more into philosophy, but for me it's fine. As long as the base is solid, for me it's fine. Aikido is a whole. I think that it's good if we can draw the largest public possible. I personally feel quite comfortable with anybody.

Guillaume Erard with Jacques Payet and Reg Sakamoto

Guillaume Erard with Jacques Payet and Reg Sakamoto

Guillaume Erard: That's it really. Aikidoka are often criticized for the contradictions in the system, but many people don't realize that it is precisely the point of the whole thing. It's a system that has practically unsolvable intrinsic contradictions, and that's the whole point of studying the system.

Jacques Payet: Right. And what's important are the principles. How can we apply the principles, not the techniques.

Guillaume Erard: You have known Japan in the 80's. You have lived in Japan for a long time. You returned to Europe, to the US, and now you are again settled in Japan, so you saw the country change, and necessarily, so did aikido, because in principle, aikido adapts to the needs of the society in which it is being practiced. What are the fundamental changes in Japanese society that affected what we do on the tatami, more than anything else?

Jacques Payet: I think that society got more westernized. At the time, when I was in Musashi-Koganei, it's outside Tokyo, the dojo was at 30 minutes walk, but whether it was summer or winter, many people came to the morning class. And on the tatami, nobody talked, it was very serious. Respect for... It was true budo. The atmosphere was almost like that of a church or a temple. It was a special place and people came for that, you could feel it everywhere. Little by little, people, students, started to be more like in France, Europe or the US, they're more relaxed, they ask questions: "How do you do this technique?" whereas before, no one would dare asking a question. It was "osu" and you would practice. Today it's much more relaxed, I don't know whether it's a bad thing, I think there needs to be some balance, because id it's too stern like this, it's difficult to learn... Especially with aikido, where it's about learning to relax, to feel oneself, so if we're like that, it's difficult. But if we don't have this intense and focus aspect, almost some fear, if we haven't been through that experience, it's very difficult to really produce that exceptional force. There needs to be that balance.

Guillaume Erard: It definitely comes from within. At the moment, because of the Covid-19, I haven't been at the Aikikai Hombu Dojo for a while, and I know that when I return, like every time, I will have that pressure, almost fear, as I pass the Ueshiba family house and enter the building. Nothing is going to happen to me of course, but I put myself under such pressure, such expectations, that it leads to this feeling, and I think that it is essential when one studies budo. On the contrary, I am convinced that people who go to Hombu casually don't anywhere get as much out of training.

Jacques Payet: I agree.

Guillaume Erard: When you were young, very early on, you wanted to become a priest, right?

Jacques Payet: Yes. When I was 10 or 11, I wanted to become a priest, yes. So my parents put me into a seminary, but I didn't expect such a rustic life, a bit like in a dojo, really. I was too young for that, so after a month, I ran away. [laughs] I never spoke about it again.

Guillaume Erard: It was at La Reunion?

Jacques Payet: Yes, it was at La Reunion, in the mountain...

Guillaume Erard: It must have bee quite peculiar...

Jacques Payet: It was completely isolated in the mountain. The comfort was minimal. For a 10 year-old child, getting up at 5 a.m. and take a cold shower — because there was no hot water —, having to eat like everybody else... Whims were not welcome, it was life in a community. You had to do the chores, etc. so I wasn't ready for that at all.

Guillaume Erard: From a certain point, you went back to that sort of life when you became an uchi deshi didn't you?

Jacques Payet: That's right.

Guillaume Erard: So it was really something that you had in you...

Jacques Payet: Yes, I think that it was something in me. I was never someone violent... I don't know... I'm not particularly good material for martial arts, I think. That's why I think that aikido suits me well.

Guillaume Erard: Was there any sort of spiritual research or did you only seek austerity?

Jacques Payet: I think that it was a spiritual search, that's why I said that I was lucky in what I did, because I've known two aspects of Shioda Sensei. When I arrived, he was 63 years old, exactly my age today. He was still very physical, he was very stern. It was no joke, "bam! bam!" Everybody was scared, there was electricity in the air when he was here, so this really shaped me. It stayed with me. I did that for five years and I left. It taught me to never give up, a sort of willpower that I could never have gotten without that environment, but I don't think I learned much about aikido. The only thing I learned was to do a very strong shihonage... [laughs] and going "bam!" Nobody dared to extend their arm because they were sure that they'd be hurt. Everybody was like this. The aikido I learned during those five years was like that: "bam!".

Shioda Gozo awarding a certificate to Jacques Payet during his farewell party (December 1985)

Shioda Gozo awarding a certificate to Jacques Payet during his farewell party (December 1985)

It was very interesting when I returned to France, nobody did that, there was only Muguruza, but he had a very tiny dojo, besides, it was in Paris and I was in Lyon. Because I had done ju-jutsu and karate before, I went back to my old friends who did that, and I saw that aikido didn't work. Because people didn't know how to take ukemi, and if they resisted a bit, it didn't work. So it allowed me to really question myself and to think about this.

Then, during my second stay in Japan, Shioda Sensei was much older, — he was 70 or 75 years old — he was much more... — how to say this? — He didn't lose his strength, but his strength had taken a very different aspect. It was almost like ki. There was something that emanated with much more kindness. It was an aspect that I didn't know. So that second time, I really focused on him. I forgot all I had learned until then, I started from scratch. That allowed me to really observe how he walked, how he moved, what he was doing when he was in his office... I was 100% focused on him. That's how I completely changed my way of training, my way of thinking, and that's how I developed something much more personal.

Guillaume Erard: What you're saying about watching his way to walk and to move is very striking for me because I have a very similar experience with my own Daito-ryu teacher, Chiba Tsugutaka. I finally understood ikkajo/ippondori on the day I understood how he walked.

Jacques Payet: Right.

Guillaume Erard: Before that, I saw an old man who almost lost his balance forward, — especially when he was doing ippondori — until the day where I realized that it was his way of moving, of transferring his body... From the moment I saw that, what I used to consider as a mistake, something not to do, I realized that it was the motor of his technique. On the other hand, in complete opposite, we sometimes have the tendency to mimic the mannerisms of our teachers that are absolutely not necessary.

Jacques Payet: That's right.

Guillaume Erard: Do you think that it's that second experience that opened your eyes?

Jacques Payet: Yes.

Guillaume Erard: Because coming back is never done in Japan usually.

Jacques Payet: It doesn't happen, I'm the only one. That's right, if I hadn't returned, my aikido would have been completely different. Really different.

Guillaume Erard: I'm tempted to draw the parallel with O Sensei's deshi, who might have missed something since they only had one go at it, before they went abroad.

Jacques Payet: Yes. Yes, because there is this evolution, and for me, it's the whole that is important. If we know only about this period or that period, and we are unable to link them, it's difficult to get the whole picture. So I think that both were necessary. If I had only seen the second part, it wouldn't be the same.

Guillaume Erard: You would have interpreted it differently.

Jacques Payet: Completely differently. It's because I was lucky enough to have both that I could take it all in, and do something personal.

Guillaume Erard: Can we describe it in terms of progression, though it may not be the adequate term... Perhaps differences in Shioda Sensei's aikido according to his age and experience?

Jacques Payet: Oh yes. I think that when he was younger, it was really almost brutal. It was an almost brutal force that exploded, so it would hurt. He could have killed his uke with that sort of power. Towards the end of his life, it was much more controlled, much more artistic... It was the same power but you no longer felt it. What really surprised me is that, he would do irimi and could strike you, but it left no mark, so I would fall without knowing why. There was practically no contact. It's just that the timing was so perfect that there was almost no impact, but I was on the floor.

What really interested me in that aikido is that when I was there the first time in the 80's, I was always on guard, so when I took ukemi for an instructor, I could feel the hit, "bam!" But at the end of Shioda's life, we fell almost by ourselves. So we were surprised: "Why did I fall?", it was strange, so we laughed. We laughed because we wondered what happened, it was strange. That feeling, that's the aikido I want to do, because I think that anybody is able to throw hard. But to make it so that the person doesn't even realize what happened, she's surprised, it's a completely different feeling.

Guillaume Erard: Can we talk about clemency in that case?

Jacques Payet: I think so, yes.

Guillaume Erard: If we want to get to that level, we need to actively not want to hurt...

Jacques Payet: You need a determination and a constant focus, so that we can let go of that energy. It's a constant, daily work. We can't suddenly relax and do magic, without having paid the price, or put in the effort.

Guillaume Erard: We see that a lot though, within the Aikikai, for sure, you just have to go to the Budokan every year to see people who think they are O Sensei, and obviously, they aren't. But what surprised me a lot is that in Daito-ryu too, you see people do those rather incredible things and you wonder... Chiba Tasugutaka, who when he was alive, was above pretty much everybody else, — in terms of seniority, I'm not making a judgement of value — would laugh when he saw that being done by other senior Daito-ryu instructors.

Jacques Payet: It's the ground work that's really important. Simply, a technique, to be really effective, it needs to be the consequence. It's not really the result. It's because we've worked for all that time, we made so much effort, we worked so much, that the body naturally learns the correct posture and the perfect timing and because those elements are together, the technique works.

Guillaume Erard: We talked about spirituality, we talked about almost monastic experiences, and things like that... Did you ever look into the Omoto aspect of aikido?

Jacques Payet: I don't know... My wife teaches at the university, and her subject is Shintoism, so she did some research into Omoto and we talked a bit about it, but I never really looked into it... I should, because the Omoto center is here in Kyoto, and it could be interesting indeed. But I must confess that I'm not sure I'm really interested in that.

Guillaume Erard: About the neo religions?

Jacques Payet: Yes.

Guillaume Erard: Quite frankly, it's the same for me, and to do that, you really need to know old Japanese and have really immersed yourself in it. However, I really feel that the universalist goals of Omoto really transpired on aikido.

Jacques Payet: Yes.

Guillaume Erard: I don't think that the Aikikai in particular, and perhaps the other branches too, could have developed internationally like that if there hadn't been with the tacit agreement from the founder as regards to opening it up. In Daito-ryu, that wasn't the case, and it still is quite limited. We always say that aikido = Daito-ryu + Omoto, and the main contribution of Omoto is, in my opinion, it universalist goal. What interests me in particular is to find out what are the consequences of this universalist aspect on the diffusion aikido outside of the cultural and historical context in which it was formulated by O Sensei. Indeed, we said earlier that aikido had to be relevant in the context in which it was being practiced. So, how important is Japanese culture, when we practice aikido?

Jacques Payet: I think that, at the level of the Yoshinkan, it's a taboo subject because Shioda Sensei didn't like at all this religious, Omoto aspect. I often heard him say: "I have a huge amount of respect for Ueshiba Sensei, his techniques are wonderful but he was a bit weird and I never understood and was never interested in all of this religious, Omoto aspect." So I think that for the Yoshinkan, this religious or spiritual aspect doesn't exist. It's the technique. You need a very good base, you need to be strong, and you need the spirit. The "yoshin", that's it.

Especially in France, for example, I think that aikido would never have spread as much as it did if there hadn't been that philosophical aspect. I think that it attracts a lot of Europeans, and French people in particular.

Guillaume Erard: The romanticized version of it.

Jacques Payet: Right. I think that's it, perhaps that's why. Of course, for Ueshiba Sensei's personality, his technique, etc. but I think that it played a very important role for the expansion of aikido in the world.

Guillaume Erard: Did Shioda Sensei talk a lot about O Sensei?

Jacques Payet: Yes, especially when he had had a drink. [laughs] He talked a lot about him. He still had a lot of respect for him, he was his teacher. Whenever he did a demonstration, he always talked about his past and about Ueshiba Sensei.

Guillaume Erard: Because the Yoshinkan was created while O Sensei was alive, which is pretty unusual, unavoidably, there must have been some levels of competition, perhaps for media's attention, etc. I always wonder how that happened.

Jacques Payet: From what I understood, I think that the first Yoshinkan dojo was opened in Shinjuku in 1955. At that time, Ueshiba Sensei was no longer in Tokyo and Kisshomaru Sensei was still working, so the Hombu was still there but it was being used for other things. At some point, the US army used it as a dance place and things like this, and there were very few students, so at this point, I think that Shioda Sensei, who had to take care of his family, who needed to work, so he became very active. He visited the police, he did a lot of demonstrations, and most importantly, in 1953-54, he was part of one of the first kobudo demonstrations. Many bankers and sponsors were there, and they liked his demonstration, so it's from that point that he could start his dojo.

He was very active from that time, while at the Aikikai, Kisshomaru Sensei was still working, and the other deshi were not really active, so for five or six years, the Yoshinkan increased, it took the lead. After that, it was quickly caught up by the Aikikai when Kisshomaru quit his job and dedicated himself fully to the Aikikai.

Guillaume Erard: I'd like to get back for a bit on the history of techniques. The Yoshinkan nomenclature is still: "ikkajo, nikajo, sankajo, and so on..." Also, Shioda Gozo was one of the people who were sent to Osaka to teach in the 1930's, at the time of the Asahi Journal, and most likely, in other places too, and from all the sources we have, we know that it was pure Daito-ryu at the time. When we look at the Daito-ryu curriculum, in particular the 118 techniques of the hiden mokuroku, we find most of the techniques of aikido that we know. It's possible that Kisshomaru Sensei might have decided, while O Sensei was alive, to take some of the Daito-ryu techniques to build the Aikikai curriculum: "Let's take ippondori and let's call it ikkyo." He took one from the 30 techniques of Daito-ryu's ikkajo. He took one from the 30 techniques of Daito-ryu's nikajo and called it nikyo. However, I'm always surprised about the degree of similarity between the program of the Yoshinkan and that of the Aikikai. I always wonder where that selection of a few techniques taken from the Daito-ryu curriculum comes from, and what is the meaning in terms of the logic of its organization, pedagogically. Did Shioda Sensei explain that when he taught?

Jacques Payet: Not really. All he said was that Ueshiba Sensei didn't have a very pedagogical way to teach. He showed the techniques once and said: "Do it". Then the student replicated it. There was practically no way for a student, except an uchi deshi or someone who looked very carefully, to remember the technique and progress in a systematic way. When he created the Yoshinkan, he mostly wanted to have a system so that the students could progress, so he chose 150 techniques, he separated them systematically, and he developed the Yoshinkan system. So it must have been a mix. He took from Ueshiba's repertoire, he took what he thought was the most important, and he put it in place, in that system.

Guillaume Erard: Besides that use of a different suffix "kajo" instead of "kyo" ?

Jacques Payet: Right.

Guillaume Erard: This system looks quite similar to that of the Aikikai.

Jacques Payet: Quite.

Guillaume Erard: When we talk about ikkajo in Yoshinkan aikido, are we talking about a technique on one particular attack, or is everything ikkajo?

Jacques Payet: No, everything is ikkajo, shomen, yokomen, katate, hiji, kata, ushiro... Same for nikajo.

Guillaume Erard: Then the question that follows is: If we have the five kajo, that we often translate in French, especially when we use the suffix "kyo", as "principles". What of kotegaeshi, shihonage, why aren't those deserving to be called "principle"? What does it mean in the Yoshinkan system?

Jacques Payet: [laughs] I never asked myself that question! [laughs] I don't think that there is a particular meaning. I think that he just took what already existed and he put it in place. I don't think he thought much about it.

Guillaume Erard: Then what about in the technical progression, is there a set of techniques that a beginner at the Yoshinkan will learn first, and then others?

Jacques Payet: Yes. Generally, they start with shihonage, the first technique, shihonage, ikkajo, nikajo, sankajo, yonkajo, then, iriminage, and it goes up like this.

Guillaume Erard: OK. That's interesting because one of my Daito-ryu teachers, Kobayashi Kiyohiro, who trained at the Aikikai and at the Yoshinkan while Shioda Sensei was alive, told me the the closest thing to Daito-ryu in terms of aikido, from his perspective as a Daito-ryu practitioner who reluctantly had to do aikido, it's at the Yoshinkan that he found the closest things.

Jacques Payet: Yes, I was quite surprised when I attended the class of Kondo SenseiKondo Katsuyuki, a senior student of Takeda Tokimune, and the head of the Daito-ryu main branch in Kanto. in Las Vegas, it was the same techniques. Perhaps a little more brutal but... [laughs]

Guillaume Erard: And in terms of his pedagogy, if the technique was similar, what about the pedagogy itself, was there a difference?

Jacques Payet: No, it was quite similar. He marked some pauses, and then restarted, it was quite similar.

Guillaume Erard: OK. There is something that created a bit of a stir a while ago, and which Ellis Amdur looked into, it is the connection between Horikawa KodoHorikawa Kodo (堀川幸道, 1894-1980) was a student of Takeda Sokaku and a prominent instructor of Daito-ryu aiki-jujutsu and Shioda Gozo. Of course, it was a little before your time. Did you witness relations between the Yoshinkan and the Kodokai?

Jacques Payet: No. When i was there though, I think that I saw once, the visit of the Daito-ryu Sensei but it was just a visit of courtesy, they were in suits, there was no practice at all. So I think they just maintained relationships like that.

Shioda Gozo with Horikawa Kodo at the Yoshinkan Headquarters (c. 1978)

Shioda Gozo with Horikawa Kodo at the Yoshinkan Headquarters (c. 1978)

Guillaume Erard: In the martial arts world, all of those people knew each other.

Jacques Payet: They knew each other.

Guillaume Erard: They were often together. We think that there are clean separations, and every time we see a connection we think: "Wow!" But in fact no, they were often together.

Jacques Payet: Right, it was the same generation.

Guillaume Erard: They lived very close to each other.

Jacques Payet: Every time we did the Yoshinkan's annual demonstration, all sorts of personalities were there, Mas Oyama, Nakayama, there were judoka and many people came.

Guillaume Erard: Regarding the role of aikido, what you think the purpose of aikido is? What do you think that aikido brought to your life, which no other activity could have brought? Either another martial art, or even something else completely. In other terms, what is so specific to aikido, whether it is Shioda Sensei's aikido, or that as imagined by Ueshiba Sensei, or your own practice. What is it that makes it aikido, and not something else?

Jacques Payet: I'll answer at a personal level, just for myself. The experience I have from other martial arts, whether it's jujutsu or karate, kung fu, a bit as well... Those are quite defensive postures. You're always a bit on the defensive. What I like with aikido is that it's an opening, an opening on others. It allows a different relationship with others. It's more of a relationship of trust than a relationship of defense. How to say this? It opens up a different perspective. We see ourselves and we see others in a different way. In terms of aikido, it allows to become together one and the same person. This dualistic aspect disappears. The fact of having this physically, it applies also in everyday life with people around us. Naturally, we go towards people, we open up towards others. Especially in today's world, where people have a tendency to be like: "Who the heck are you?" to take our distance, I think that it's really important. It's this human side, which is very precious and that must be developed. We shouldn't be afraid of the other and to close ourselves, especially in moments of difficulty, of problems, on the contrary, we have to open up. How to say this? To go beyond oneself and reach out to others. I think that Aikido can really help a lot in that.

Guillaume Erard: To conclude, it's very interesting for me to hear this from you, knowing that the image of the former uchi deshi of the police program of the Yoshinkan is a bit of an image of blood thirsty brutes, savages. [laughs] But in the end, we realize that after 40 years of practice, you also aim for this opening, a desire to foster positive values via aikido, an acceptation of different forms of practice, which is quite surprising and also quite good for our discipline. So on this topic, to finish, what is your hope for the future of aikido, and the direction in which you see it go? What is it important to keep, knowing that aikido is by definition a bit proteiform and that it will adapt to the circumstances? What should we keep in all this?

Jacques Payet: I think that the most important is to find a way to dream in aikido. It mustn't only be a self defense discipline, or for physical health, there needs to be something that gives hope and dreams, so that we want to practice, because this is something special, that will truly make a difference in the world. It's that spirit that I would like the students to keep. Because if that little flame is there, for me, the most important thing for the coming generation it's that there is a sort of alchemy, that they start aikido for whatever reason, and that there is a little thing inside that changes, that transforms itself, so that what used to be a simple stone there, becomes a small diamond.

But there needs to be something that creates a desire to walk the journey, because it's not an easy journey. We have to go one step at the time, we need a lot of energy and focus, we must be ready to give always more, not to receive, but to give, because it's more important. In aikido, the more we give, the more we receive. So we shouldn't want to train only to become strong, or to do extraordinary things, we should train to become able to open up more and more, so that we can give more and more, and the more we give, the more we'll receive. It has to be a message of hope.

Guillaume Erard: Jacques Payet, thank you very much.

Jacques Payet: Thank you very much for this opportunity.

Many tanks to Reg Sakamoto for coming up with the idea of this interview and for facilitating the meeting.