In this article series, we are investigating the secret scrolls of Daito-ryu, looking for the hidden roots of Aikido. In the first three parts, we have been focusing on the first scroll, Daito-ryu jujutsu hiden mokuroku (大東流柔術秘傳目録). In Part 1, we analyzed its technical content and identified techniques that later became basic techniques in Aikido. In Part 2, we focused on the lineage written in the scrolls as well as the origin story of Daito-ryu as it was told by Takeda Sokaku. In Part 3, we investigated Takeda Sokaku’s basic Daito-ryu curriculum and saw how it has developed in modern Daito-ryu and Aikido circles.

In this article, we are going to look into the second transmission scroll of Daito-ryu, the hiden okugi no koto that was awarded to Ueshiba Morihei in 1916.

Hiden okugi no koto (秘傳奧儀之事) literally translates as “Matters of the Secret Mystery”. Just like hiden mokuroku, this scroll existed from the very beginning of Takeda Sokaku’s teaching career of Daito-ryu jujutsu to the general public (i.e. 1899).

Segments of Iwafuchi Giemon’s hiden okugi no koto awarded in November 1899, four months after the first ever Daito-ryu training was recorded in Sokaku’s eimeiroku (see the evidence in Part 1).

Segments of Iwafuchi Giemon’s hiden okugi no koto awarded in November 1899, four months after the first ever Daito-ryu training was recorded in Sokaku’s eimeiroku (see the evidence in Part 1).

The hiden okugi no koto was awarded after hiden mokuroku and it represents a higher level of transmission in Daito-ryu. Ueshiba Morihei received this scroll from Sokaku in March 1916, following his participation in a series of Sokaku’s seminars held in Hokkaido (see more details in Part 3, as well as our companion article investigating training durations).

The content of Ueshiba Morihei’s scroll was first published in the book Nihon Budo Zenshu Vol. 5 (日本武道全集 第5巻) in 1966, while he was still alive, and later, the pictures of the actual scroll where made public in the “Aikijutsu” chapter of the book Nihon Budo Taikei Vol. 6 (日本武道大系 第6巻), which was written in 1982 by Morihei’s son and successor, Ueshiba Kisshomaru.

Ueshiba Morihei’s hiden okugi no koto scroll awarded by Takeda Sokaku Minamoto no Masayoshi in Shirataki, Hokkaido, in March 1916. Pictures from Nihon Budo Taikei Vol. 6, Aikijutsu Chapter written by Ueshiba Kisshomaru in 1982.

Ueshiba Morihei’s hiden okugi no koto scroll awarded by Takeda Sokaku Minamoto no Masayoshi in Shirataki, Hokkaido, in March 1916. Pictures from Nihon Budo Taikei Vol. 6, Aikijutsu Chapter written by Ueshiba Kisshomaru in 1982.

The scroll is similar in structure to that of the hiden mokuroku, starting with items (條) of technical notes, followed by a short transition text, and concluded with the lineage of the Takeda family. The technical notes are arranged in two parallel lines. Two items describe one technique, the upper one states the attack or situation, and the lower one the defensive move. The numbering goes up to 18 in both lines, adding up to 36 items in the scroll altogether. Unlike in the hiden mokuroku, kakete or offensive techniques (Item 8 and 18) are also written as two items. What immediately stands out is that compared to the hiden mokuroku, the technical descriptions are longer, revealing more specific details and hints for each technique.

The following table summarizes the content of the scroll:

| Attack | Defense | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Yokomen-uchi | shiho-nage |

| 2 | Kata-dori | Sankajo |

| 3 | Muna-dori | Throw forward |

| 4 | Ryote-dori | Kote-gaeshi |

| 5 | Sode-dori | shiho-nage (Ura) |

| 6 | Yubi-dori | shiho-nage (Ura) |

| 7 | Ushiro Sode-dori | shiho-nage |

| 8 | (Uchikaiten) Sankajo (pin to knee) | |

| 9 | Ushiro Suso-dori | shiho-nage |

| 10 | Hands in the sleeves | shiho-nage |

| 11 | Yonin-dori | Throw |

| 12 | Kasa-dori | Throw forward |

| 13 | Jo sabaki | shiho-nage (Ura) |

| 14 | Jo sabaki | shiho-nage |

| 15 | Draw the short sword | Tessen (Uchikaiten) Sankajo nage |

| 16 | Grab the handle of the sword | shiho-nage |

| 17 | Newaza Sannin-dori | Throw forward |

| 18 | Kote-gaeshi |

Looking through the list, we can see that some of the techniques also appear in the hiden mokuroku. However, within the hiden okugi no koto, they are described with a different "higher-level" finishing variation.

Although this scroll mentions fewer techniques in number, it introduces interesting new situations that are not described in the hiden mokuroku. For example, yokomen-uchi (striking the side of the head), grabbing various parts of the kimono, techniques against three and four opponents, and weapon variations using jo (staff), sword, and short sword as well as tessen (iron fan). While relatively few techniques in hiden mokuroku were ascribed the following an additional note: “torihanashi no koto (取放シノ事)”, instrucitng to release the opponent at the end of the technique, it is indicated to do so for all of the hiden okugi no koto techniques.

Shiho-nage

Similarly to the hiden mokuroku, shiho-nage is the most frequently represented technique in the hiden okugi no koto. Item 1 describes shiho-nage from a yokomen-uchi attack. As we mentioned before, yokomen-uchi was not mentioned in hiden mokuroku and it appears here for the first time, suggesting that it was considered a more advanced level of practice in the old curriculum. In contrast, nowadays, yokomen-uchi shiho-nage is practiced as a basic technique in AikidoThe knowledge of this technique is expected from 4th kyu onwards, according to the Hombu Dojo grading system. as well as in some modern Daito-ryuIn the Horikawa line, it is practiced as early as shodan level. On the other hand, in Takeda Tokimune’s modern Aiki-budo, it is found in the sankajo part of the curriculum, which usually corresponds to a sandan level.. The technique is described as follows:

第一條

Item 1

一、 右手ニテ横ヨリ打ツ事

Strike with the right hand from the side.

第一條 取放シノ事

Item 1 Release the opponent

一、 敵ノ手首ヲ内ヨリ左手ニテ摑ミ目カクシヲ打敵ノ右手ヲ左ニ下ゲ左足ヲ敵ノ右ヨリ左ニ入敵ノ手首ヲ両手ニテ摑ミ頭上ニアゲテ右ノ足ヲ後ヘ引キ投ル事

Grab the opponent’s right wrist from inside with the left hand, strike the eyes, lower the opponent’s right hand to the left, step in with the left foot from the opponent’s right to his left, grab the opponent’s wrist with both of your hands, raise it above your head, pull the right foot back while throwing.

The description ends as tori pulls the right foot back while throwing uke (右ノ足ヲ後ヘ引キ投ル事). This execution of the shiho-nage also appears in item 7, 9, 10, and 16. This way of throwing is not described in the hiden mokuroku, suggesting that was a higher level and actually a more dangerous variation that is a characteristic of the hiden okugi scroll.

Takeda Tokimune demonstrating two ways of throwing shihonage. On the top, tori leaves the leg closer to uke in the front while throwing as shiho-nage is described in Sokaku’s hiden mokuroku scroll. At the bottom, tori pulls back that leg and throws uke straight down as it first appears in Sokaku’s hiden okugi no koto scroll. Note that here Tokimune Sensei demonstrates katate-dori shiho-nage from his Ikkajo set of 30 techniques. It seems that in modern Daito-ryu the two ways of throwing are taught from ryote-dori as omote and ura variations from the beginner level.

Takeda Tokimune demonstrating two ways of throwing shihonage. On the top, tori leaves the leg closer to uke in the front while throwing as shiho-nage is described in Sokaku’s hiden mokuroku scroll. At the bottom, tori pulls back that leg and throws uke straight down as it first appears in Sokaku’s hiden okugi no koto scroll. Note that here Tokimune Sensei demonstrates katate-dori shiho-nage from his Ikkajo set of 30 techniques. It seems that in modern Daito-ryu the two ways of throwing are taught from ryote-dori as omote and ura variations from the beginner level.

In item 1, for yokomen-uchi, tori blocks uke’s right hand with the left hand and applies an atemi with the right hand without stepping away. It seems that the technique developed with time, and an initial backward step was added, moving out of the reach of the attack.

In Ueshiba Morihei’s Budo Renshu from 1933, the description of yokomen-uchi shiho-nage starts as:

Block with the left hand, pull the left foot back and strike the (opponent’s) face with the right (hand)...”

左手で受け左足を引き右で面うつ...

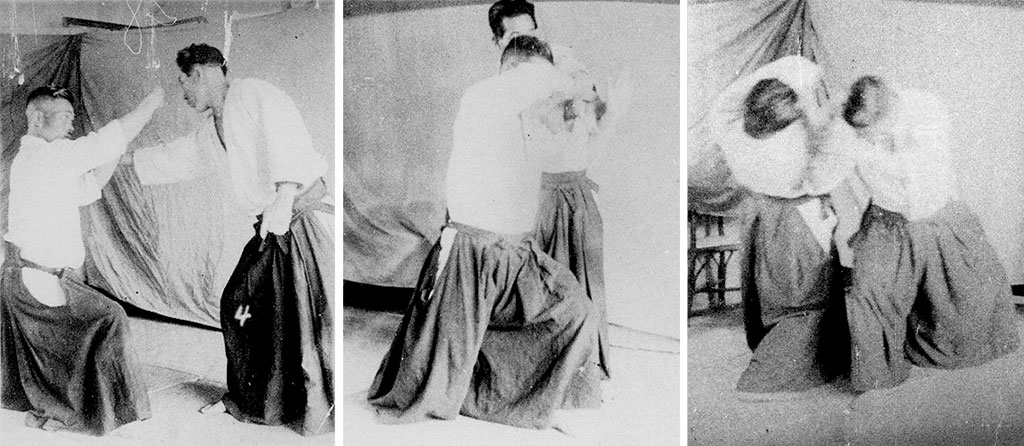

Illustrations of yokomen-uchi shiho-nage from Ueshiba Morihei’s Budo Renshu from 1933. On the left, tori controls uke’s attack with the left hand and executes an atemi with the right hand while stepping backward, In the middle, tori grabs uke’s wrist with both hands and executes the throw on the right. The red arrows indicate the movement of the left foot. Note that tori is not stepping back with the right foot at the end.

Illustrations of yokomen-uchi shiho-nage from Ueshiba Morihei’s Budo Renshu from 1933. On the left, tori controls uke’s attack with the left hand and executes an atemi with the right hand while stepping backward, In the middle, tori grabs uke’s wrist with both hands and executes the throw on the right. The red arrows indicate the movement of the left foot. Note that tori is not stepping back with the right foot at the end.

After stepping back with the left foot, tori steps forward staying nearly on the same line during the whole technique. A similar execution of shiho-nage is demonstrated in the Soden photo collection as well.

Yokomen-uchi shiho-nage from Soden Vol 3. demonstrated by Yoshimura Yoshiteru.

Yokomen-uchi shiho-nage from Soden Vol 3. demonstrated by Yoshimura Yoshiteru.

In the previous article, we took a look at Tokimune Takeda’s basic Daito-ryu Aiki-budo curriculum also known as hiden mokuroku 118 kajo. We saw that his system of 118 techniques does not only consist of techniques written in Takeda Sokaku’s hiden mokuroku scroll, but also of includes techniques from other (higher level) scrolls. For example, yokomen-uchi shiho-nage which is the first item in Sokaku’s hiden okugi no koto scroll, is included in the sankajo set in Tokimune’s modern Daito-ryu Aiki-budo curriculum of 118 techniques.

Yokomen-uchi shiho-nage from the sankajo set of Tokimune’s hiden mokuroku 118 techniques. Tori steps back with the left foot then forward as can be seen in various prewar Daito-ryu and Aikido documents. Note that with the first step, atemi to the opponent’s face is omitted.

Yokomen-uchi shiho-nage from the sankajo set of Tokimune’s hiden mokuroku 118 techniques. Tori steps back with the left foot then forward as can be seen in various prewar Daito-ryu and Aikido documents. Note that with the first step, atemi to the opponent’s face is omitted.

As we have seen, in Daito-ryu and prewar Aikido, yokomen-uchi shiho-nage was defended while stepping backward. On the other hand, Ueshiba Morihei’s techniques developed after the war in a more circular manner as we can observe in the numerous surviving video footage of the Founder from this period. In the case of yokomen-uchi, tori does not step backward anymore but rather steps forward and turns while executing an atemi. This step is called irimi-tenkan or tenshin in modern Aikido and has become the most common way of yokomen-uchi practice in Aikikai Aikido.

Ueshiba Kisshomaru demonstrating yokomen-uchi shiho-nage. Illustrations from the book "Aikido" published in 1963.

Ueshiba Kisshomaru demonstrating yokomen-uchi shiho-nage. Illustrations from the book "Aikido" published in 1963.

Shiho-nage ura techniques (tori turns to uke’s side) are described in item 5 for sode-dori (grabbing the sleeve) and in item 6 for yubi-dori (grabbing the fingers).

Sankajo

In the hiden mokuroku, all sankajo (sankyo in Aikido) techniques are performed with tori moving under uke’s arm (uchi-kaiten sankyo in Aikido) (左ニテ敵ノ右手ヲ押ヘ右ノ足ヲ敵ノ右ニ入レ頭ヲ越シ右ニ抜ケ...) while in item 2 of the hiden okugi no koto the sankajo grip is described for the first time through just switching the hand position (...敵ノ手首ヲ右ノ手ニテ摑ミ直ス事).

-

Illustrations of sankajo from the Soden photo collection Vol 3. On the left, a kakete variation of sankajo where tori grabs uke’s left hand with the right hand and moves under uke’s arm (uchi-kaiten). On the right, for kata-dori, tori grabs the back of uke’s hand with the right hand and removes uke’s grasp like ikkajo but immediately re-grasps uke’s wrist with the other hand to sankajo.

Illustrations of sankajo from the Soden photo collection Vol 3. On the left, a kakete variation of sankajo where tori grabs uke’s left hand with the right hand and moves under uke’s arm (uchi-kaiten). On the right, for kata-dori, tori grabs the back of uke’s hand with the right hand and removes uke’s grasp like ikkajo but immediately re-grasps uke’s wrist with the other hand to sankajo.

Similarly to Item 18 of hiden mokuroku, Item 8 of hiden okugi no koto describes a kakete (i.e. offensive technique) variation of sankajo where tori grabs uke’s hand and moves under uke's arm (uchi-kaiten). While in hiden mokuroku the most common way of performing sankajo is to pin the uke’s hand to his lower back, Item 8 describes a more advanced variation where tori pins the uke’s hand to the back of the knee.

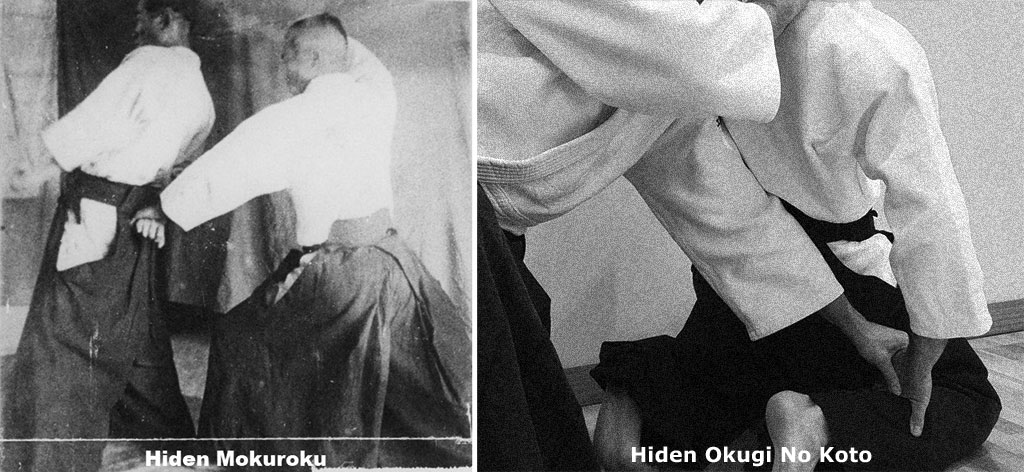

Sankajo pinning the uke's hand to the back of the hips (on the left) and to the back of the knee (on the right) as described in hiden mokuroku and hiden okugi no koto, respectively.

Sankajo pinning the uke's hand to the back of the hips (on the left) and to the back of the knee (on the right) as described in hiden mokuroku and hiden okugi no koto, respectively.

Kote-gaeshi

Item 4 describes kote-gaeshi from a ryote-dori attack while standing. We have seen that ryote-dori kote-gaeshi is decribed from a sitting position in the hiden mokuroku (Item 8 in the zatori section). In the hiden okugi no koto, similarly, kote-gaeshi is executed while grabbing uke’s thumb, however, the initial kashiwade (hand clap) is not mentioned, which was probably a more basic execution of the technique. It seems that in the early years of Daito-ryu (1900s), kote-gaeshi was executed while grabbing uke’s thumb, and later it developed into a way where tori, instead of grabbing the thumb, places his hand on the top of uke’s hand and cuts it down.

On the left, the older form of kote-gaeshi, grabbing uke’s right thumb with the left hand as described in hiden mokuroku and hiden okugi no koto scrolls. On the right, the later version of kote-gaeshi where tori places the left hand on the top.

On the left, the older form of kote-gaeshi, grabbing uke’s right thumb with the left hand as described in hiden mokuroku and hiden okugi no koto scrolls. On the right, the later version of kote-gaeshi where tori places the left hand on the top.

In the basic Daito-ryu curriculum, for katate-dori and ryote-dori kote-gaeshi, tori grabs uke’s wrist from below with the same hand (left-hand grabs the left wrist).

Katate-dori and ryote-dori kote-gaeshi in Daito-ryu. Tori grabs uke’s left wrist with the left hand from below (“gyaku” kote-geashi grab in Aikido), taking control of uke’s wrist joint immediately. Note that tori doesn’t step away during the technique.

Katate-dori and ryote-dori kote-gaeshi in Daito-ryu. Tori grabs uke’s left wrist with the left hand from below (“gyaku” kote-geashi grab in Aikido), taking control of uke’s wrist joint immediately. Note that tori doesn’t step away during the technique.

On the other hand, for Tsuki, Shomen-uchi, and Yokomen-uchi, tori grabs uke’s wrist from above with the opposite hand (left-hand grabs the right wrist).

Tsuki kote-gaeshi in Daito-ryu. Illustrations from the Soden Photo Collection Vol. 3.

Tsuki kote-gaeshi in Daito-ryu. Illustrations from the Soden Photo Collection Vol. 3.

In Daito-ryu, both ways are called kote-gaeshi, however, in Aikido the first way is sometimes distinguished as “gyaku” kote-gaeshi.

We have seen in part 3 of this article series that Takeda Sokaku developed a system of basic techniques that had five levels. In his system, he taught a particular pinning technique (ikkajo to gokajo), applied to various attacks. In addition, variations and throwing techniques were added to his seminar curriculum but only for specific attacks. For example, ryote-dori kote-gaeshi was included in the ikkajo seminar curriculum, and tsuki kote-gaeshi probably in the nikajo one.

In his teaching, Ueshiba Morihei kept Sokaku’s overall logic of applying the same technique from different possible attacks. Building on this method, the Aikido curriculum includes the five basic pinning techniques (ikkyo to gokyo) as well as five basic throwing techniques (shiho-nage, irimi-nage, kote-gaeshi, kaiten nage, and kokyu-ho (sokumen irimi-nage)), all taught from all possible attacks in the basic curriculum. More specifically, in the case of kote-gaeshi, the second way, where tori grabs uke’s wrist from above with the opposite hand, became systematized.

Katate-dori kote-gaeshi in Aikido. Tori cuts of uke’s grasp with the right hand and re-grasp uke’s wrist with the left hand from above.

Katate-dori kote-gaeshi in Aikido. Tori cuts of uke’s grasp with the right hand and re-grasp uke’s wrist with the left hand from above.

Thus in the basic Aikido curriculum, for katate-dori and ryote-dori, tori cuts off uke’s grasp and re-grabs uke’s wrist from above. This execution (cut and re-grab) probably didn’t exist in Sokaku’s curriculum and the development of the Ueshiba Morihei. The “gyaku” kote-gaeshi that was the basic for katate and ryote attacks in Sokaku’s system is still practiced in Aikido but as variation (応用変化 applied technique).

Ueshiba Kisshomaru demonstrating katate-dori “gyaku” kote-gaeshi as an applied technique. Note that in Aikido body movement is applied and tori steps to the side during the technique.

Ueshiba Kisshomaru demonstrating katate-dori “gyaku” kote-gaeshi as an applied technique. Note that in Aikido body movement is applied and tori steps to the side during the technique.

Item 18, the last technique in the scroll, describes a kakete (offensive technique) variation of kote-gaeshi. Tori initiates with an atemi to the opponent’s eyes, grabs the opponent’s wrist with the other hand, and twists it down. Kakete kote-gaeshi is also included in the hiden mokuroku, but in the zatori (seated techniques) section.

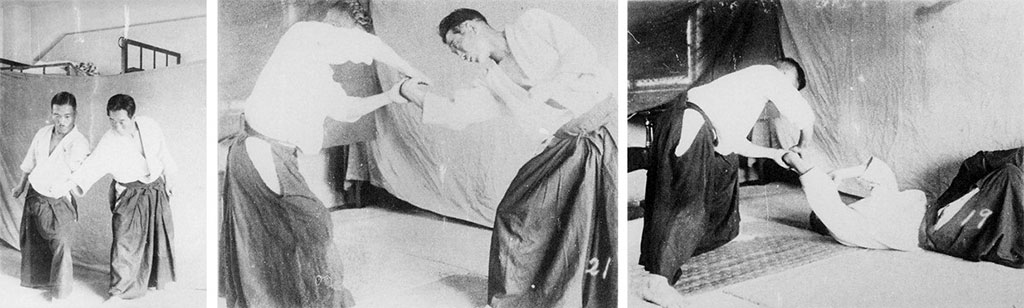

Kakete (attacking) variations of kote-gaeshi from the Soden photo collection, while sitting (left) and in standing (right).

Kakete (attacking) variations of kote-gaeshi from the Soden photo collection, while sitting (left) and in standing (right).

Multiple Attackers

The hiden mokuroku describes three techniques against two opponents, followed by a note pertaining to the cases when one faces three or four opponents, stating that the technique must be done based on the same principle. The hiden okugi no koto actually describes a technique dedicated for this situation.

Item 11 is a yonin-dori technique where four people control one person; two people grab the left and right arms, one person grabs the chest with two hands, and one person grabs the back of the opponent’s collar. In this response, tori grabs the left opponent’s wrist with the right hand and the right opponent’s wrist with the left hand, pulls them together, raises the hands, and throws the opponents.

A different but a similar yonin-dori technique is often demonstrated by Kondo Katsuyuki, Somucho of the Tokimune-line.

Yonin-dori in Daito-ryu, demonstrated by Kondo Katsuyuki Somucho. In this technique, tori grabs the right uke’s wrist with the right hand and the left uke’s wrist with the left hand applying yonkajo. Then moves the uke on the right around and piles uke on each other.

Yonin-dori in Daito-ryu, demonstrated by Kondo Katsuyuki Somucho. In this technique, tori grabs the right uke’s wrist with the right hand and the left uke’s wrist with the left hand applying yonkajo. Then moves the uke on the right around and piles uke on each other.

In the Horikawa line, yonin-dori is also practiced in a sitting position called denchu-waza (殿中技, techniques for use inside a palace). These techniques are usually done without re-grabing the opponents’ wrists (jujutsu) and require advanced Aiki skills.会津藩殿中御式内の謎 by Nomoto Tadashi, Hidden Magazin, 2023 March

Horikawa Kodo demonstrating a yonin-dori technique from sitting in 1980, a few weeks before his death.

Horikawa Kodo demonstrating a yonin-dori technique from sitting in 1980, a few weeks before his death.

Item 17 describes a technique against three opponents, however, in this specific situation, tori is pinned down to the ground; one person holds down tori’s chest with two hands, and two people control the left and right hands with two hands. In response, tori grabs the right opponent’s left wrist with the left hand, and the chest of the opponent’s on the top with the right hand pulling the three opponents together. Then, kicking the opponent’s back on the top, tori throws the three opponents forward (above the head).

Takeda Tokimune demonstrating a ne-waza technique from a situation being pinned down by not three but five opponents. Illustrations from Daito-ryu Hokei by Takeda Tokimune.

Takeda Tokimune demonstrating a ne-waza technique from a situation being pinned down by not three but five opponents. Illustrations from Daito-ryu Hokei by Takeda Tokimune.

Kasa-dori

Kasa-dori techniques start from a situation where uke grabs the shaft of the umbrella that tori’s holding. In hiden mokuroku there is one technique mentioned in such a situation where tori grabs uke’s wrist and executes a shiho-nage throw. In item 12 of hiden okugi no koto, similarly, tori re-grabs uke’s wrist but puts uke's arm on the shoulder and throws forward like udekime-nage in Aikido. Note that the same forward throw is described in Item 3 for muna-dori attack, while hiden mokuroku contains shiho-nage for the same attack.

Jo techniques

The scroll describes two jo techniques, where uke grabs the opposite end of the jo that tori’s holding. In Item 13, tori grabs uke's left wrist with the left hand and turns to uke’s side to apply a shiho-nage ura throw. On the other hand, in Item 14, tori grabs uke’s right wrist with the left hand and moves under the arms executing a shiho-nage throw. The scroll is very specific about the fact that tori grabs uke’s wrist during the throw making it a Jujutsu technique. However, in the later Daito-ryu and Aikido curriculums, tori usually throws uke without grabbing uke’s wrist, exclusively using uke’s grasp on the jo, making it an Aiki application of the technique.

Ueshiba Kisshomaru demonstrating shiho-nage using a jo. Note that uke is thrown as he is grabbing the tip of the jo.

Ueshiba Kisshomaru demonstrating shiho-nage using a jo. Note that uke is thrown as he is grabbing the tip of the jo.

Sword techniques

The last technique in the hiden mokuroku scroll was shiho-nage from a situation where uke grabs the handle of the sword that is in tori’s belt. In this case, tori locks the tsuba with the left hand and grabs uke’s right wrist with the right hand, moves under uke's arm, and executes the throw. In item 16 of hiden okugi no koto, the same shiho-nage technique is written for this situation, however, with the mention that tori pulls the right foot back while throwing that is the characteristic of shiho-nage of the hiden okugi level as we have seen above.

Tessen techniques

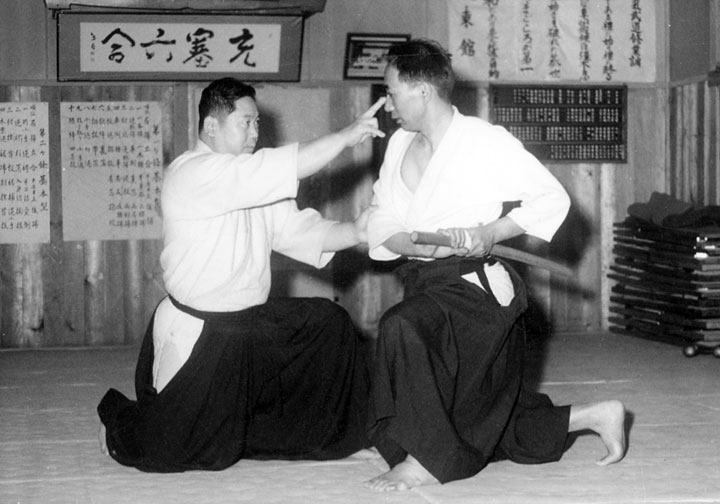

Item 15 describes a technique where uke is drawing a wakizashi (脇差, short sword). In response, preventing uke from fully drawing the blade, tori grabs uke’s right wrist with the left hand and hits the uke’s eyes with a tessen (鉄扇, iron fan). Then tori controls the wakizashi’s handle with the iron fan and applies an (uchikaiten) sankajo throw on the right hand.

Takeda Tokimune demonstrating a technique against an opponent drawing a short sword at Daitokan dojo, Abashiri, Hokkaido. In this technique, he uses his fingers to attack the opponent’s eyes.

Takeda Tokimune demonstrating a technique against an opponent drawing a short sword at Daitokan dojo, Abashiri, Hokkaido. In this technique, he uses his fingers to attack the opponent’s eyes.

In the Meiji era, people were not allowed to wear swords in public anymore. As a martial artist of that era, Sokaku always carried an iron fan or other concealed weapons preparing for any extreme situations. It seems he liked to use tessen in the dojo too as we can see in the few surviving pictures of him demonstrating Daito-ryu techniques.

Takeda Sokaku holding a tessen in his right hand. In his early years (left) and in action in his 80s (center and right).

Takeda Sokaku holding a tessen in his right hand. In his early years (left) and in action in his 80s (center and right).

Sokaku often presented iron fans or other weapons to his students.

Takeda Sokaku’s tessen on the left and the one Sokaku presented to Ueshiba Morihei on the right that is displayed in the Shirataki village museum.

Takeda Sokaku’s tessen on the left and the one Sokaku presented to Ueshiba Morihei on the right that is displayed in the Shirataki village museum.

Ueshiba Morihei frequently demonstrated techniques using a fan against sword and spear attacks as is compiled in this video:

Unfortunately, these techniques disappeared from the modern Aikido curriculum.

Transition text

The technical descriptions in hiden okugi no koto end with a note 計三拾六ヶ條 右奥儀御信用之手 meaning “total 36 items, all on the right are Mistery Goshinyo no Te techniques”.

In hiden mokuroku we have seen that not all of the 118 items were explicitly written in the scroll. In hiden okugi no koto, however, all 36 items are written describing 18 techniques and these techniques are called “goshinyo no te”. The literal translation of the characters is “techniques of trust”, or loosely “techniques that can be trusted”. Interestingly it is also a homophone of the term used for self-defense techniques (護身用之手). Actually, Daito-ryu was often promoted as self-defense by Sokaku and his students.1930 Ima Bokuden ArticleSato Sadami Joshi Goshinjutsu (Woman Selfdefense) published in 1917Kawamata Kozo, Gokui Hiden Goshinjutsu Kyojusho (Secret Self-defense Textbook) published in 1932)Hisa Takuma Joshi Goshinjutsu (Woman Self-defense)

In older scrolls, there was an additional note following as 参拾六ヶ條堅ク可相守事, meaning that these “36 items must be protected strictly”, however, this note was removed probably in the late 1900s or early 1910s.

A segment of Takegawa Gijuro’s hiden okugi no koto scroll awarded by Takeda Sokaku in July 1905. The note that the “36 items must be protected strictly” is highlighted in red. The same note can be seen in Iwabuchi’s scroll from 1899 as it is shown above. In the following transition text, the characters of "nesshin" (熱心, enthusiasm) are marked in yellow.

A segment of Takegawa Gijuro’s hiden okugi no koto scroll awarded by Takeda Sokaku in July 1905. The note that the “36 items must be protected strictly” is highlighted in red. The same note can be seen in Iwabuchi’s scroll from 1899 as it is shown above. In the following transition text, the characters of "nesshin" (熱心, enthusiasm) are marked in yellow.

The technical notes are followed by a transition text written exclusively in Chinese characters (漢文, kanbun) that is added to all Daito-ryu scrolls and certificates. The text translates as follows:

This scroll is awarded to acknowledge the progression of the thorough practice of Daito-ryu Jujutsu without neglecting enthusiasm in training. Please fulfill the mastery of the techniques of sure victory through friendly rivalry without a doubt.

This kind of text is very common in koryu scrolls, where the phrase “shushin asakarazu” (執心不浅) was originally frequently used, meaning “without neglecting devotion”. This phrase is actually written in the oldest known Daito-ryu scrolls from 1899. However, in later scrolls, a different word “nesshin” (熱心, enthusiasm) is used instead of “shushin” written with very similar characters. This change was probably unintentional and an outcome of an error of copy that probably occurred in the early 1900s and has been duplicated ever since.

The transition text in both hiden mokuroku and hiden okugi no koto mentions Daito-ryu Jujutsu as the name of the art. Indeed, in these scrolls, all techniques are done by tori grasping uke’s wrist or clothes, indicative of Jujutsu, and the term Aiki is not mentioned at all.

Historical Context

We have shown that the hiden okugi no koto describes many situations where uke grabs tori’s clothes. For example, muna-dori (grab the chest), sode-dori (grab the sleeve), suso-dori (grab the hem of the kimono). In addition, the hiden mokuroku contains instances of kata-dori (grab the shoulder), eri-dori (grab the collar), kubishime (choke using the collars) attacks, and more. These kinds of situations are common in jujutsu styles created in the middle to late Edo period (1651-1868). The Edo period is known as a time of internal peace, thus the grappling techniques specific to enemies wearing armor were no longer of practical use. During this era, new jujutsu techniques were developed for people wearing everyday clothes. This kind of jujutsu is usually called suhada jujutsu (素肌柔術, armorless grappling) and one of its characteristics is joint manipulation techniques. In contrast, jujutsu styles created during the Sengoku (civil wars period 1477 - 1573) and early Edo periods were designed for battlefield combat wearing armor. Common examples are Takenouchi-ryu, Kito-ryu, and Sekiguchi-ryu, and these styles are called Kaisha jujutsu (介者柔術, grappling in armor) in generalTakahashi Masaru 大東流合気剣術の謎と真相 Hiden Magazin 2005 June. In this situation joint techniques are useless. One can experiment with it by applying nikyo or kote-gaeshi on someone wearing a kendo wrist protector which would be very difficult.

- Kito-ryu jujutsu demonstration of techniques designed for combat wearing armor on the battlefield.

Instead of grabbing the wrist and applying a joint locking technique, in these styles, tori grabs the uke’s torso and breaks his balance to throw.

In contrast, the bulk of the Daito-ryu curriculum consists of joint techniques (ikkajo, nikajo, sankajo, yonkajo, shiho-nage, kote-gaeshi), and many of the situations involve grabbing the opponent’s clothes hence the base of Daito-ryu is possibly not older than the mid-Edo period. Actually, the oldest written mention we know of proving the existence of Daito-ryu is from Sokaku’s eimeiroku (enrolment booklet) in 1899 thus the most likely scenario is that Daito-ryu was created (or more precisely, that its curriculum was either compiled or that a pre-existing jujutsu style was renamed) by Sokaku based on his earlier koryu jujutsu studies. By definition, martial arts created after the Meiji Restoration (1868) are considered gendai budo (現代武道, modern budo). However, Sokaku promoted his art as an otome-ryu (お留流 secret martial art) of the Aizu clan, making it into something of prestige. Indeed, Daito-ryu techniques are often taught together with stories about samurais who used these techniques in specific situations (for example inside the palace in front of the lord, etc.). The argument for Daito-ryu being a kobudo (古武道 old budo) resides on the fact that while these situations would indeed have made sense in the old days, they were irrelevant from the Meiji era onwards, hence comforting the idea that the roots of Daito-ryu went back to the Edo period.

From the 1920s to 1940s, Ueshiba Morihei’s art gradually evolved from Daito-ryu Aiki-jujutsu into Aikido as we know it today. In Aikido, the kobudo-like special circumstances, as well as the effectiveness of the techniques, are not emphasized anymore. Rather, the techniques serve as a tool through which one can train their mind and body and build their character (人間形成) and this philosophy is indeed the unifying characteristic of all modern Japanese budoAikido, the Contemporary Martial Art of Harmony by Ueshiba Moriteru 2019.

All these things considered, the fact that the recorded history of Daito-ryu is only about 20 years anterior to that of Aikido is, indeed, rather interesting.

Sokaku’s Daito-ryu Curriculum Around the 1910s

Sokaku started teaching Daito-ryu Jujutsu in 1899 and he seemed to have awarded both the hiden mokuroku and hiden okugi no koto scrolls from that time. In the previous article of this series, we discussed that Sokaku most likely taught according to these scrolls in the early 1900s (having presumably just created them). Thus, the earliest system of Daito-ryu consisted of two levels (hiden mokuroku and hiden okugi no koto), and the entirety of this curriculum was taught in five 10-day seminars.

Later Sokaku developed new techniques and his curriculum gradually evolved. Some time between the late 1900s to the early 1910s, Sokaku introduced a system of basic techniques that had five levels from ikkajo to gokajo. While keeping with his standard 10-day seminars format, Sokaku now taught a certain pinning technique (for example ikkajo pin) from various attacks, in addition to some variations as well as some throwing techniques. The ikkajo seminar was followed by nikajo, sankajo, yonkajo and gokajo seminars. After attending these seminars, a practitioner would be awarded the hiden mokuroku scroll. All techniques beyond the basic ikkajo to gokajo seminar curriculum, such as jujutsu variations, techniques against multiple attackers, and weapon techniques were included in the hiden okugi level in the 1910s. Aiki techniques also existed in this period, however, they were not categorized as a dedicated group of techniques yet.

Takeda Sokaku’s Daito-ryu Jujutsu curriculum of the 1910s. The basic curriculum from ikkajo to gokajo was taught during five 10-day seminars after which the first scroll hiden mokuroku was awarded. After attending more of Sokaku’s seminars, and learning more advanced variations, and weapon techniques one would receive the second scroll hiden okugi no koto.

Takeda Sokaku’s Daito-ryu Jujutsu curriculum of the 1910s. The basic curriculum from ikkajo to gokajo was taught during five 10-day seminars after which the first scroll hiden mokuroku was awarded. After attending more of Sokaku’s seminars, and learning more advanced variations, and weapon techniques one would receive the second scroll hiden okugi no koto.

Ueshiba Morihei became Sokaku’s student in 1915 and he was most likely exposed to this curriculum during his training in Hokkaido. After participating in a couple of Daito-ryu seminars and inviting Sokaku to Shirataki, Ueshiba received the hiden mokuroku (date unknown) and the hiden okugi no koto in March 1916, respectively the first and second scrolls of Daito-ryu, which constituted the full transmission of Daito-ryu Jujutsu at that time. Ueshiba also awarded these scrolls to his own students in his later years.

Daito-ryu scrolls that Mochizuki Minoru received from Ueshiba Morihei in June 1932. At the top, Daito-ryu Aikibujutsu 118 kajo .Although the title is different, its content is identical to the hiden mokuroku scroll. On the bottom, hiden okugi no koto 36 kajo. Even though Ueshiba already used Aioi-ryu Aikijujutsu from 1928 to refer to his art, here, the transition text mentions Daito-ryu Jujutsu (marked in red) again. This is probably due to the fact that Mochizuki was an uchi-deshi at the Kobukan dojo in 1931 and that he actually met and took care of Takeda Sokaku when he unexpectedly appeared at the dojo.Mochizuki Minoru 道と戦を忘れた日本武道にカツ 1995. The lineage in these scrolls is abbreviated, only mentioning Ueshiba Moritaka as a student of Takeda Sokaku, former Aizu samurai.

Daito-ryu scrolls that Mochizuki Minoru received from Ueshiba Morihei in June 1932. At the top, Daito-ryu Aikibujutsu 118 kajo .Although the title is different, its content is identical to the hiden mokuroku scroll. On the bottom, hiden okugi no koto 36 kajo. Even though Ueshiba already used Aioi-ryu Aikijujutsu from 1928 to refer to his art, here, the transition text mentions Daito-ryu Jujutsu (marked in red) again. This is probably due to the fact that Mochizuki was an uchi-deshi at the Kobukan dojo in 1931 and that he actually met and took care of Takeda Sokaku when he unexpectedly appeared at the dojo.Mochizuki Minoru 道と戦を忘れた日本武道にカツ 1995. The lineage in these scrolls is abbreviated, only mentioning Ueshiba Moritaka as a student of Takeda Sokaku, former Aizu samurai.

Summary

Takeda Sokaku started teaching Daito-ryu Jujutsu in 1899 and there were two scrolls from the beginning: Daito-ryu Jujutsu hiden mokuroku and hiden okugi no koto. Ueshiba Morihei was awarded the hiden okugi no koto scroll in 1916. This scroll consists of 36 items of technical notes describing 18 techniques. Yokomen-uchi shiho-nage, ryote-dori kote-gaeshi and kata-dori sankajo are techniques that later developed into basic techniques in the Aikido curriculum. In addition, the scroll contains shiho-nage techniques from various attacks, techniques against three and four opponents, and weapon techniques using a jo, sword, short-sword, iron fan, and umbrella.

What Ueshiba Morihei learned in Hokkaido was Sokaku’s in the 1910s Daito-ryu curriculum, which was articulated upon two levels. The basic techniques were taught in five consecutive seminars from ikkajo to gokajo after which the first scroll hiden mokuroku was awarded. All advanced techniques such as jujutsu and weapon variations, as well as techniques against multiple attackers, were considered as a higher level and thus associated with the second scroll hiden okugi no koto.

Special thanks to Guillaume Erard for his help with the documentation and advice during the redaction of this article. Thank you to Josh Gold from Aikido Journal for letting us use their database. In addition, I would like to express my gratitude to Nomoto Tadashi sensei for the useful discussion and the documents he provided for this research.